Table of Contents

- Class 1 - Introduction & Overview of the Practice of Arbitration

- Class 2 - Discovery and Disclosure of Documents in International Arbitration

- Class 3 - Challenges to Jurisdiction and Tribunals

- Class 4 - Nuts and Bolts of Awards

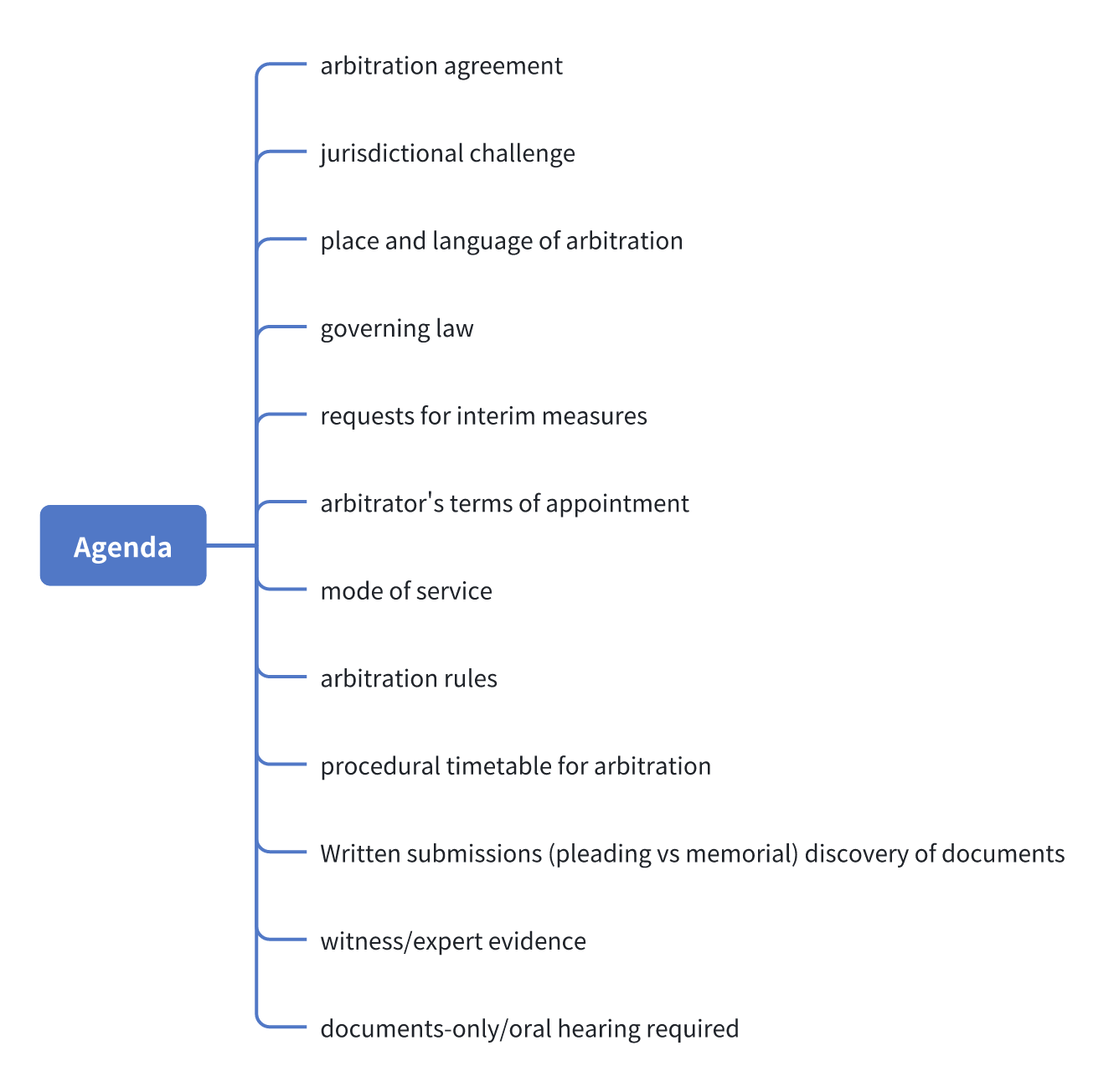

- Class 5 - Preliminary Meeting

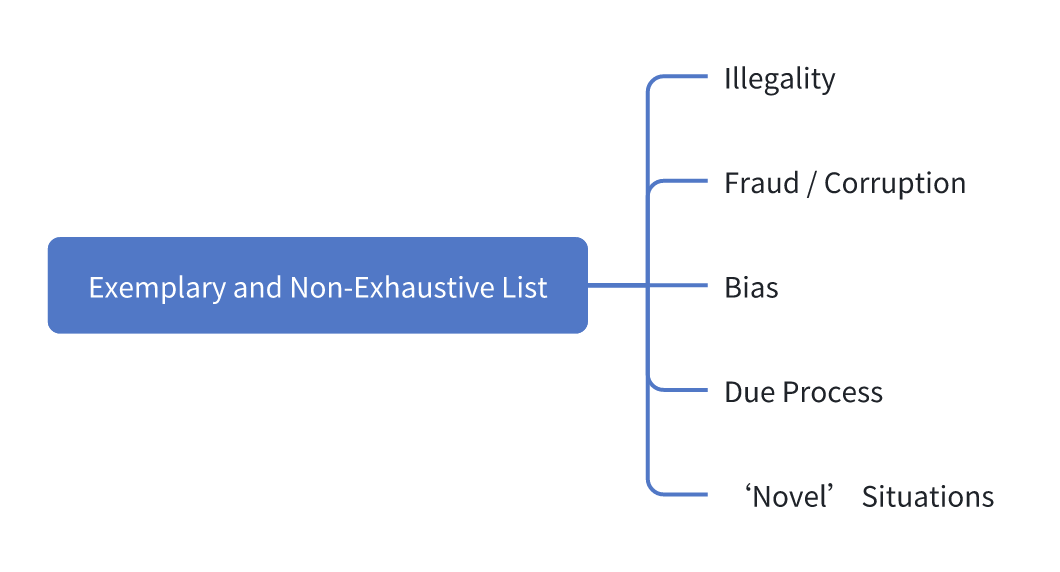

- Class 6 - Challenges to Awards and Public Policy Considerations

- Class 7 - Interlocutory Proceedings: Part 1

- Class 8 - Interlocutory Proceedings: Part 2

- I. Should relief be sought from the Tribunal or from a court?

- II. If a court, which court?

- III. Considerations for Choosing Court vs. Tribunal Relief

- IV. Interim Measures of Protection

- V. Security for Costs

- A. What is Security for costs?

- B. Questions for the arbitrator to ask:

- C. Do I have the power?

- D. How can I exercise such power?

- E. Thought Process

- F. How to determine the quantum of costs?

- G. In what form should security be given?

- H. What are the consequences for non-compliance?

- I. Timing of Security for Costs Application

- J. Practical Issues

- VI. HK/PRC Arrangement for Interim Relief in Support of Arbitration

- A. Overview of the Arrangement

- B. Practical Operation of the Arrangement

- C. Understanding the Types of Preservation

- D. Preservation Measures in Hong Kong

- E. Requirements Under the Arrangement

- F. Practical Insights: Usage and Impact

- G. Practicalities for Applicants

- H. Interim Measures in Hong Kong Arbitration: A Case Study

- Class 9 - Costs

- I. Introduction

- II. Controlling Costs

- III. Costs in Arbitration

- IV. Costs estimation and allocation

- V. Security for Costs

- VI. Cost Deduction and Reduction in Court and Arbitration

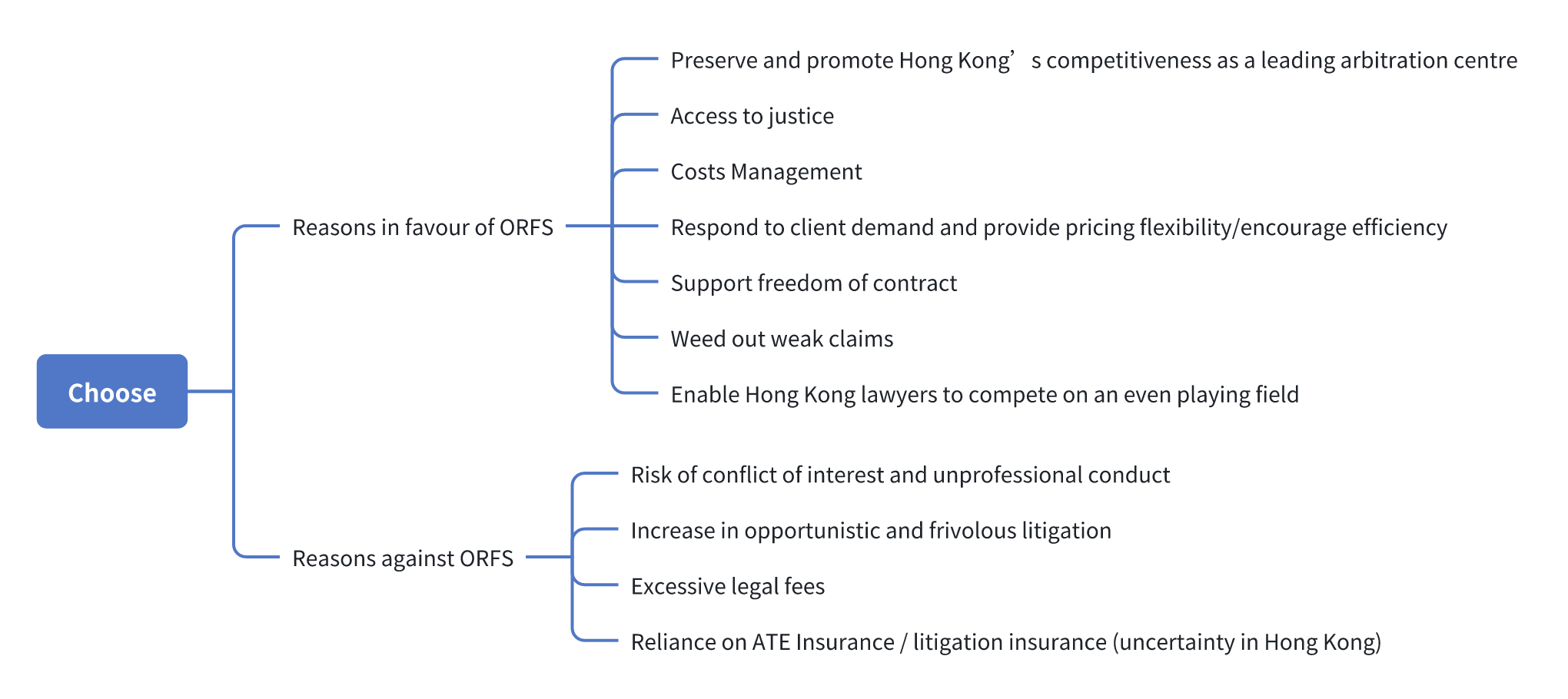

- VII. Outcome related fee structures

- VIII. Strategic and Procedural Considerations in Arbitration

- A. Initial Procedural Flaws

- B. Cost Implications and Tribunal’s Approach

- C. Jurisdictional Objections and Strategic Considerations

- D. The Importance of Full Disclosure in Enforcement Applications

- E. Key Takeaways

- IX. Cost Recovery

- A. Case Example: Minimal Success and Cost Allocation

- B. Importance of Detailed Cost Evidence

- C. Contesting Costs: The Risks of Insufficient Detail

- D. The Risk of Inadequate Cost Documentation

- Key Takeaways

- Class 10 - Interest

Class 1 - Introduction & Overview of the Practice of Arbitration

I. Dispute Resolution and the Role of Arbitration

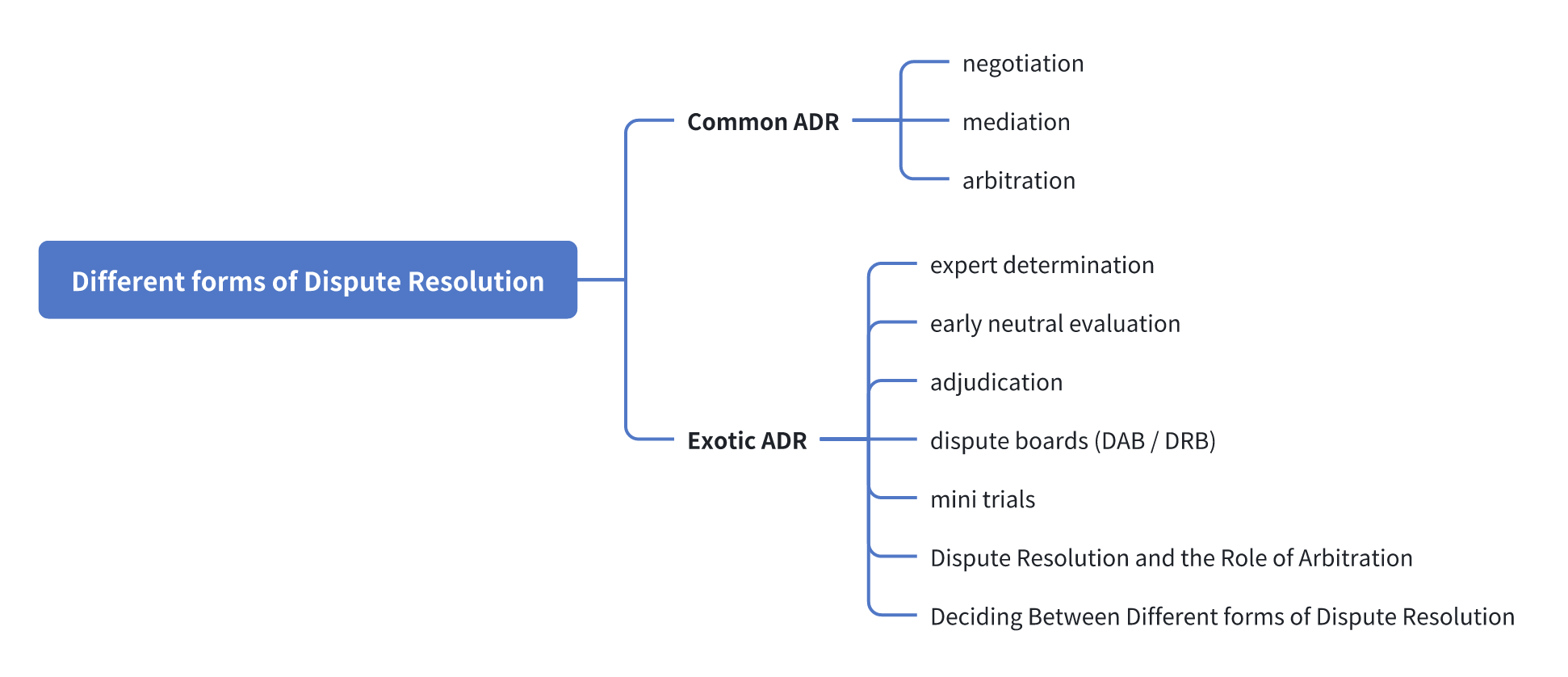

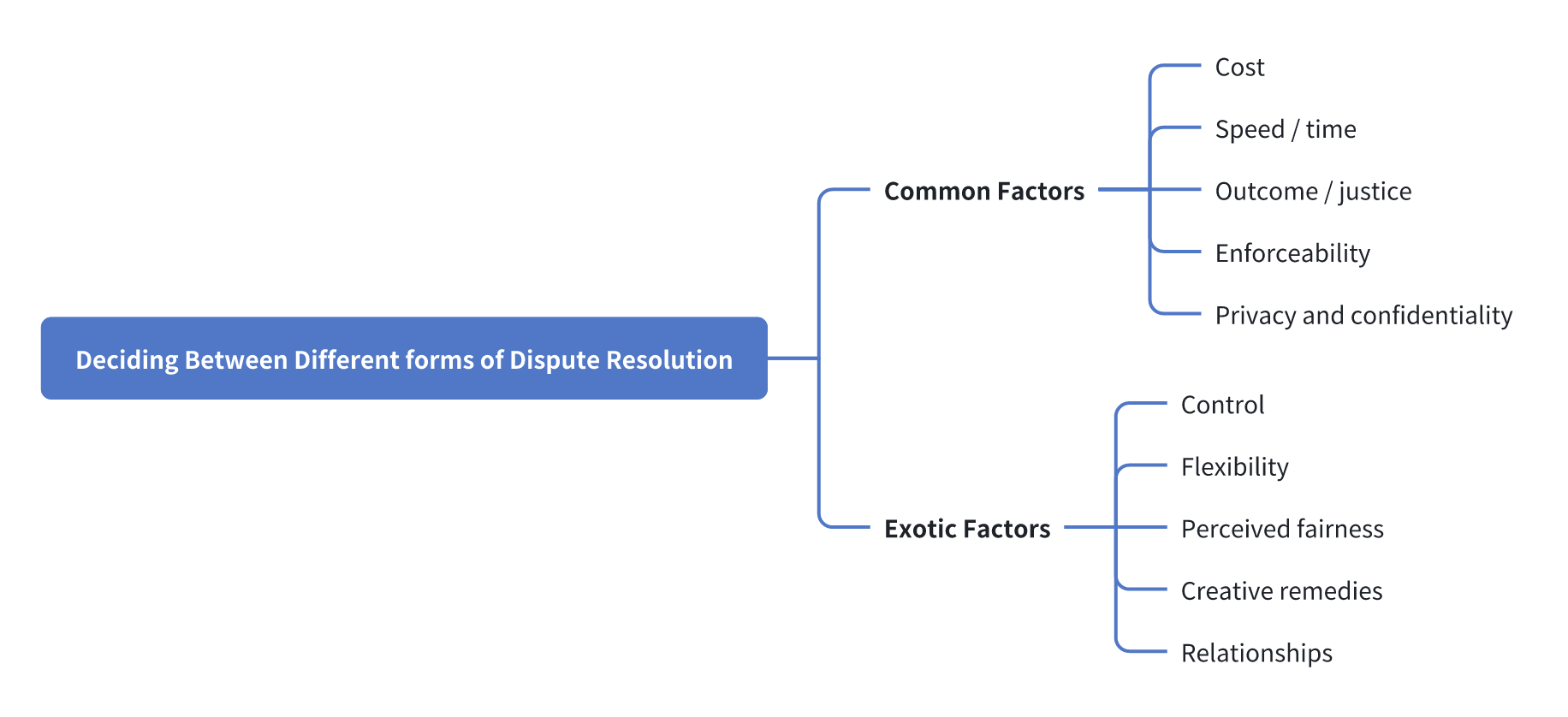

A. Different forms of Dispute Resolution

1. Arbitration

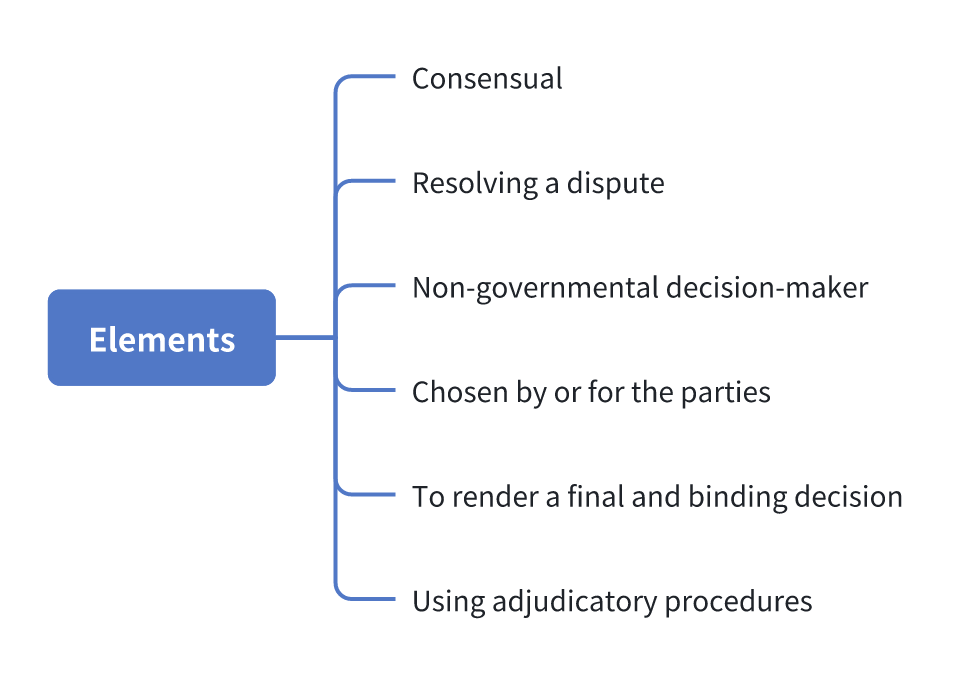

(1) Definition

International commercial arbitration is a means by which international business disputes can be definitively resolved, pursuant to the parties’ agreement, by independent, non-governmental decision-makers, selected by or for the parties, applying neutral adjudicative procedures that provide the parties an opportunity to be heard. ——G. Born, §1.02 International Commercial Arbitration (3(rd) Edition, 2021)

(2) Essential elements of arbitration

① Consensual

Arbitration is based on party agreement.

UNCITRAL Model Law Art 7(1) (Hong Kong Arbitration Ordinance sec. 19)

“Arbitration agreement” is an agreement by the parties to submit to arbitration all or certain disputes […] in respect of a defined legal relationship, whether contractual or not.

New York Convention Art II(1)

Applies to an “agreement […] under which the parties undertake to submit to arbitration”

② Resolves a dispute

Arbitration is a process to resolve a dispute, not a process for the formation of a contract, etc.

Compare HKIAC model clause for arbitration under the HKIAC Administered Arbitration Rules:

“Any dispute, controversy, difference or claimarising out of or relating to this contract, including the existence, validity, interpretation, performance, breach or termination thereof or any dispute regarding non- contractual obligations arising out of or relating to it shall be referred to and finally resolved by arbitration administered by the Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre (HKIAC) under the HKIAC Administered Arbitration Rules in force when the Notice of Arbitration is submitted.”

③ Non-governmental decision-maker

Arbitrators are non-governmental decision maker who preside over an arbitration.

They are selected by the parties. In their capacity as arbitrators they do not discharge a function or office of government or the national courts. If parties cannot agree on the arbitrators, they are appointed by arbitral institutions selected by the parties or national courts. However, duties, role and powers of an arbitrator are often regulated by national laws and courts.

④ Final and Binding

Arbitration results in a final and binding decision (award) by the decision-maker. This final and binding decision can be enforced against the unsuccessful party and its assets

Arbitration Ordinance, section 73

(1)Unless otherwise agreed by the parties, an award made by an arbitral tribunal pursuant to an arbitration agreement is final and binding both on—

- the parties; and

- any person claiming through or under any of the parties.

⑤ Use of Adjudicatory Procedures

Arbitration is an impartial adjudicatory process which affords each party the opportunity to present its case. The arbitrator’s decision is not administrative but based on the submissions and evidence presented by the parties.

Art. 18 of UNCITRAL Model Law (Arbitration Ordinance, sec. 46)

(2) The parties must be treated with equality.

(3) When conducting arbitral proceedings or exercising any of the powers conferred on an arbitral tribunal by this Ordinance or by the parties to any of those arbitral proceedings, the arbitral tribunal is required—

- to be independent;

- to act fairly and impartially as between the parties, giving them a reasonable opportunity to present their cases and to deal with the cases of their opponents; and

- to use procedures that are appropriate to the particular case, avoiding unnecessary delay or expense, so as to provide a fair means for resolving the dispute to which the arbitral proceedings relate.

(3) Advantages

- Flexibility: Arbitration is based on party agreement and can be flexible as to procedure, language, presiding arbitrators, etc.

- Confidentiality: Arbitral awards are not published and hearings are not open to the public.

- Impartiality: Wide range of competent arbitrators available with different qualifications (including foreign nationals).

- Enforceability: Arbitral awards are generally enforceable worldwide (pursuant to New York Convention – 168 member states).

- Availability of Interim Remedies: Since October 2019, parties of certain HK-seated arbitrations can apply for PRC interim relief.

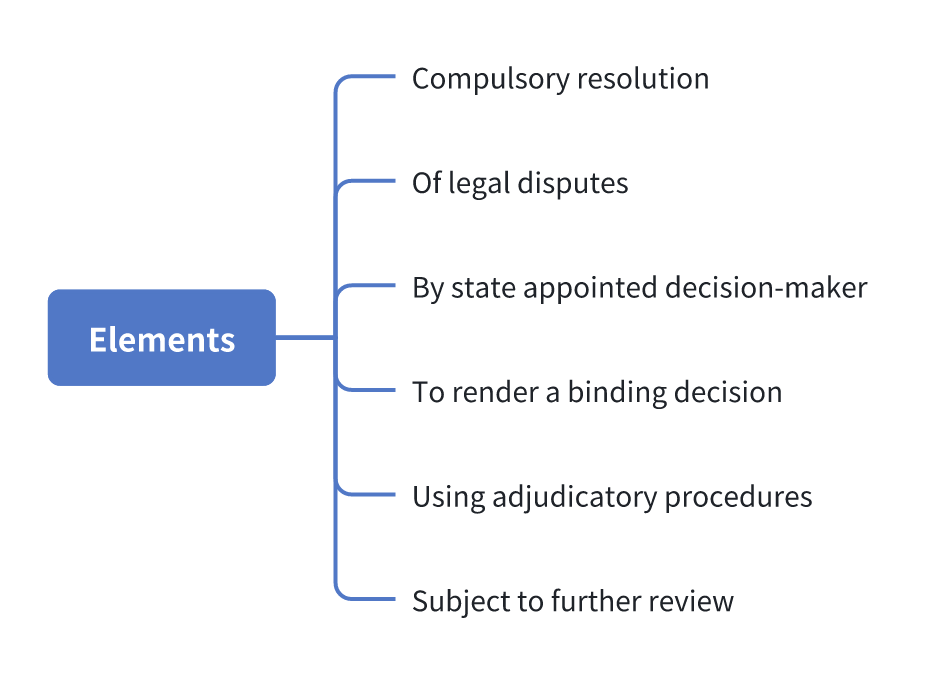

2. Litigation

(1) Elements

① Compulsory Jurisdiction

Courts exercise the jurisdiction they are given by statute, convention, history or practice. Individuals cannot ‘opt-out’ of the Court’s jurisdiction.

High Courts Ordinance (Cap 4)

- Jurisdiction of Court of First Instance

(1)The Court of First Instance shall be a superior court of record.

(2)The civil jurisdiction of the Court of First Instance shall consist of—

(a)original jurisdiction and authority of a like nature and extent as that held and exercised by the Chancery, Family and Queen’s Bench Divisions of the High Court of Justice in England; and

(b)any other jurisdiction, whether original or appellate jurisdiction, conferred on it by any law.

② Legal disputes

Courts resolve legal disputes (not social disputes or moral / ethical disputes). Courts resolve disputes according to and by applying the law.

Not _ex aequo et bono_meaning “according to the right and good” or “from equity and conscience.”

③ State Appointed Decision Makers

Governments appoint and pay decision makers (Judges). A decision maker is assigned without input from the Parties.

High Courts Ordinance (Cap 4)

4.Constitution of Court of First Instance

(1)The Court of First Instance shall consist of—

(a)the Chief Judge of the High Court; (Amended 79 of 1995 s. 50)

(b)such judges as the Governor may appoint; (Amended 80 of 1994 s. 3)

(ba)such recorders as the Governor may appoint; and (Added 80 of 1994 s. 3)

(c)such deputy judges as the Chief Justice may appoint. (Added 52 of 1987 s. 4)

④ Subject to further review

Courts usually have a system for appeals. Appeals can exist as a matter of discretion or as a matter of right

High Courts Ordinance (Cap 4)

- Appeals in civil matters

(1)Subject to subsection (3) and section 14AA, an appeal shall lie as of right to the Court of Appeal from every judgment or order of the Court of First Instance in any civil cause or matter. (Amended 25 of 1998 s. 2; 3 of 2008 s. 24)

(2) Advantages

- Enforceability: Parties can use the coercive power of the State to enforce judgments in their favour as a matter of right.

- Interim Relief: Courts use their coercive power to order interim relief against Parties and non-Parties.

- Public: Judicial proceedings are done in the open and subject to public observation and criticism.

- Certainty: The litigation process is understood and applied by qualified experts (judges and lawyers).

- Review: Judges who make mistakes can be corrected on appeal.

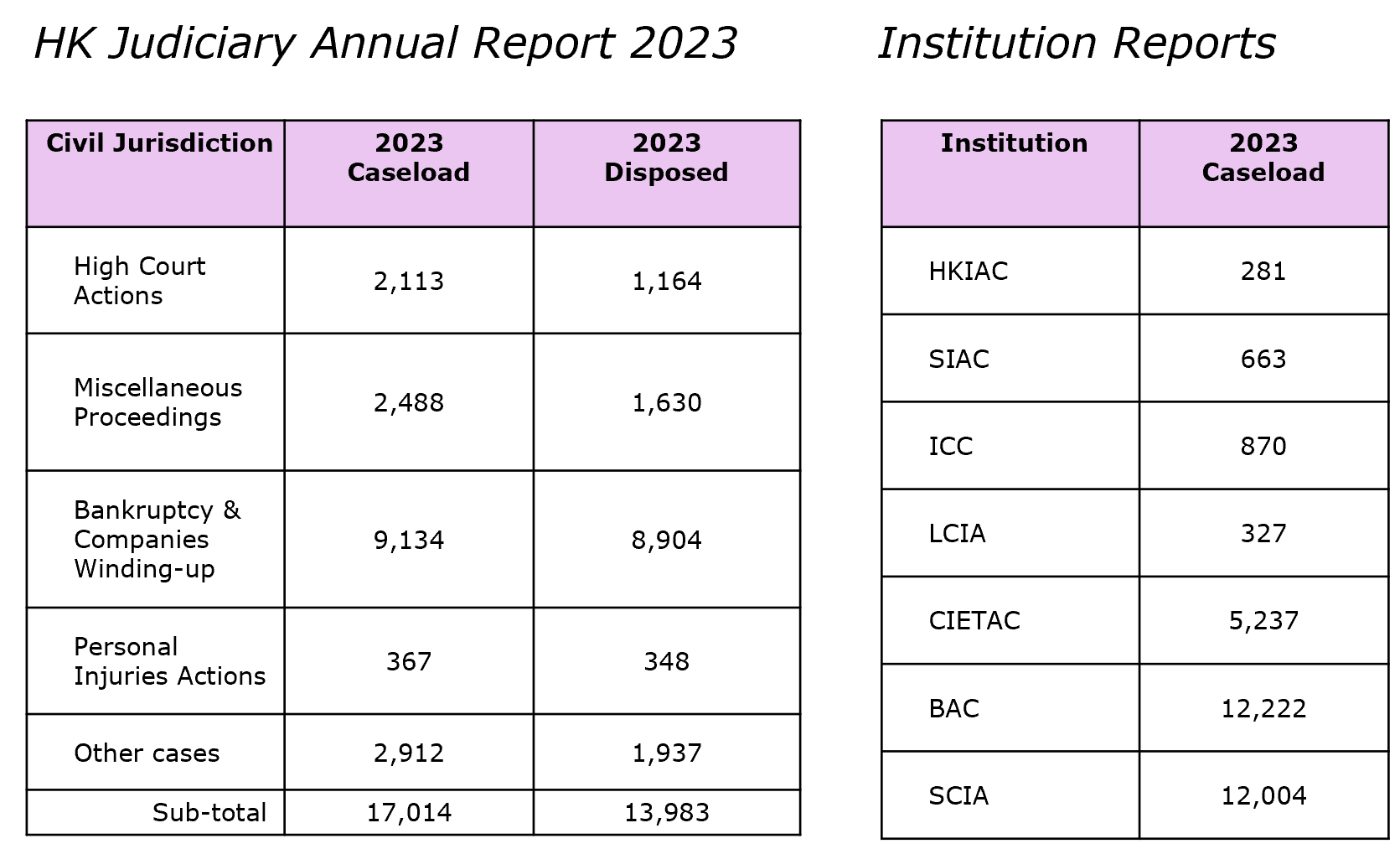

(3) Litigation & Arbitration: Statistics and Context

In 2023, arbitration institutions in China handled a total of 607,000 arbitration cases but there were 45.3m court cases.

3. Mediation

(1) Definition

Mediation Ordinance (Cap 620)

4.Meaning of mediation

(1) For the purposes of this Ordinance, mediation is a structured process comprising one or more sessions in which one or more impartial individuals, without adjudicating a dispute or any aspect of it, assist the parties to the dispute to do any or all of the following—

(a) identify the issues in dispute;

(b) explore and generate options;

(d) reach an agreement regarding the resolution of the whole, or part, of the dispute.

(2) Advantages

- Flexibility: Parties choose their mediator and decide how the mediation is conducted.

- Time / Cost saving: Mediation is usually shorter and cheaper than litigation or arbitration.

- Private: Mediation and any settlement reached are confidential to the Parties.

- Relationship: Mediation delivers mutually acceptable outcomes.

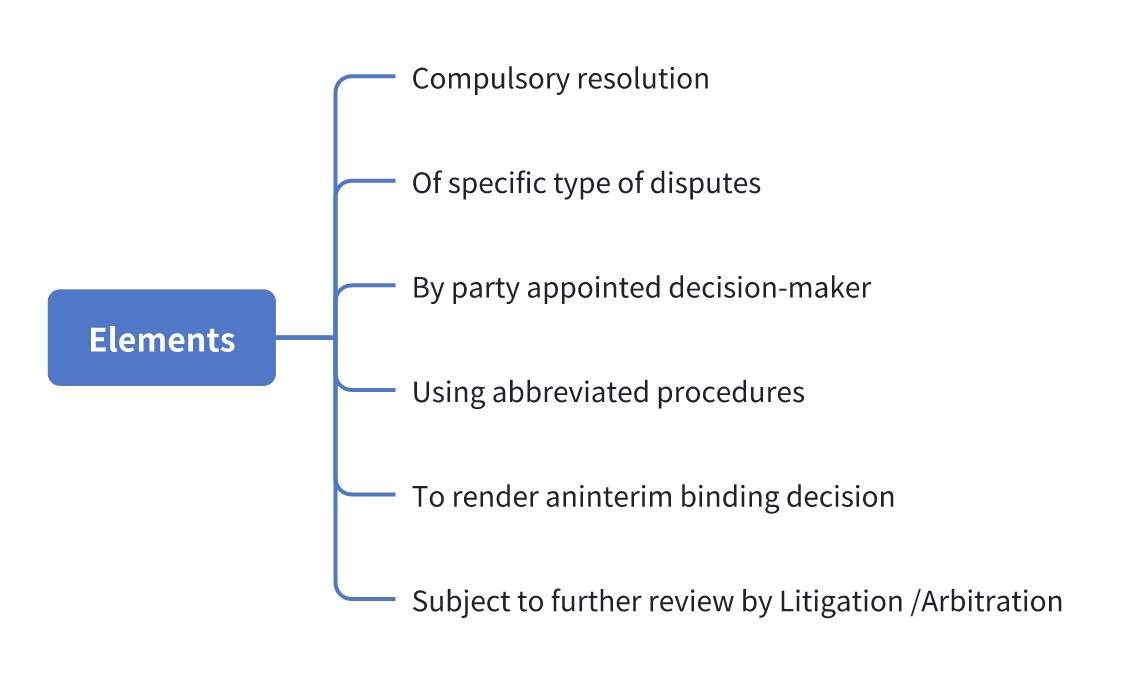

4. Adjudication

(1) Elements

(2) Advantages

- Time / Cost saving: Adjudication is usually much shorter and therefore cheaper than litigation / arbitration & the other side may not be able to claim its costs.

- Cash Flow: Quick decisions allow parties to get paid now to fund their business.

- Mandatory: If imposed by statute, no agreement needed and no ability to contract out.

- Early Communication: Avoids stalling behaviour or ignoring entitlements.

- Confidentiality: Decisions are not published and hearings are not open to the public.

- Impartiality: Wide range of competent adjudicators available with different qualifications (including foreign nationals and industry professionals).

(3) HK’s Construction Adjudication Scheme: Construction Industry Security of Payment Bill

Enacted 18 Dec 2024

Payment Scheme

- Payment Claim by the contractor (s. 18)

- Payment Response in 30 days (s. 20)

- Adjudication starts within 28 days (s. 24)

- Determination within 55 days (unless extended by agreement) (s. 42(5))

Determinations

- Cover payment claim and costs of adjudication (not representation costs) (s. 42(1))

- Be in writing and contain reasons (s. 42 (6))

- Given by adjudicator to ANB and by ANB on the parties (s. 42(5) & (7))

- Binding unless set aside by the Court, settlement or court / arbitration decision (s. 44)

B. Different ways of dispute resolution and how they compare

Litigation | Arbitration | Mediation | Adjudication | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Jurisdiction | Local law & civil procedure / Conflicts of Law Rules | Party Agreement | Party Agreement | Contract and/or statutory procedure |

Governing Procedure / Rules of Evidence | Local civil procedure laws | Flexible | Flexible | Prescribed by contract / statutory procedure |

Governing Law | Default: Local law | Flexible | Flexible (decision making not necessarily based on legal principles) | Flexible |

Confidentiality | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Appeal | Yes | No | No | Maybe |

Enforceability | Yes | Yes | Yes | Maybe |

Interim Relief | Yes | Yes | No | No |

II. Arbitral Institutions: Drivers of Change?

A. Basic Questions

1. Institutional Arbitration v. ad hoc Arbitration

- Institutional Arbitration: Proceedings conducted under administration of an arbitral institution with its pre-formulated arbitration rules.

- Ad Hoc Arbitration: Proceedings of which the parties select the arbitrator(s), the rules and procedures, and organize the process.

2. What is an arbitral institution?

…a permanent organization to which parties to a dispute reserve some decisional authority in order to facilitate an arbitration conducted in accordance with a set of arbitration rules. —— The Functions of Arbitral Institutions, Rémy Gerbay (2016)

B. The role of Arbitral Institutions

Arbitral institutions play an important role in organizing and overseeing arbitration proceedings. They provide a set of rules and administrative support to ensure the process runs smoothly. Here’s a brief breakdown:

- Administering Arbitrations: Arbitral institutions help by managing the logistical aspects of the arbitration process, including appointing arbitrators, coordinating hearings, and managing documentation.

- Providing Rules and Procedures: Institutions offer standardized rules (like the ICC Rules or SIAC Rules) that guide the arbitration process, helping parties to understand the procedure and expectations from the outset.

- Offering Expertise: They can provide a pool of experienced arbitrators who are experts in specific fields, which is crucial for complex disputes.

- Ensuring Neutrality and Fairness: The institution’s role is to ensure the process is fair and neutral, especially in cross-border disputes where there might be concerns over bias or lack of familiarity with the local legal system.

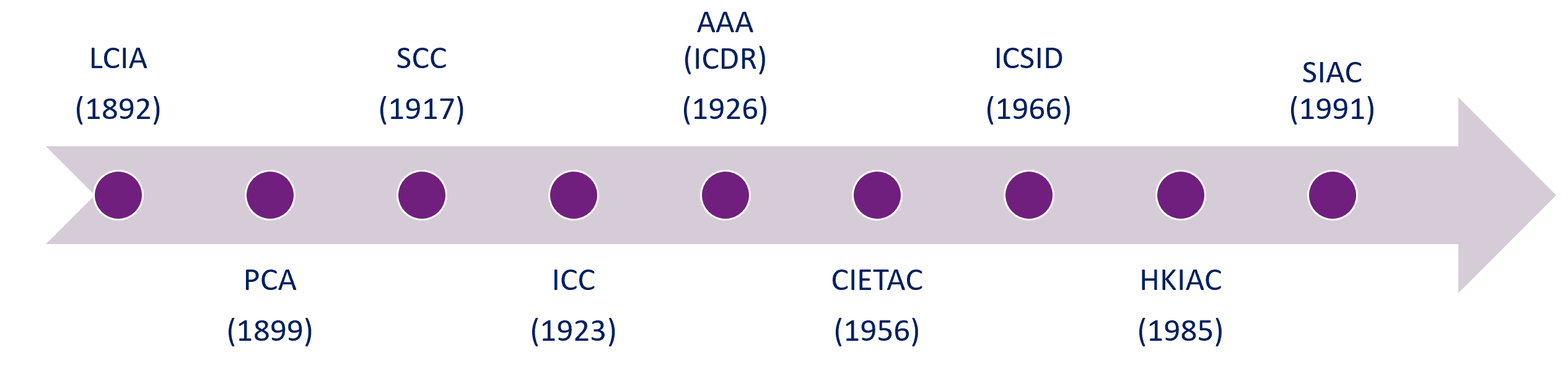

C. The Rise of the Arbitral Institution

Arbitral institutions began forming in the late 19(th) Century as a means of facilitating and administering arbitral proceedings.

Alphabet soup: ICC, SIAC, HKIAC, CIETAC, MCIA, KCAB, LCIA, SCC, ICSID, PCA etc. These institutions are known collectively as the “alphabet soup” of arbitration because of their wide range of acronyms.

Initially, arbitration was primarily used for resolving commercial disputes between businesses. However, over time, it expanded to include investor-State and State-to-State arbitration, especially with the rise of international trade and investment.

Growth and rise of institutions: As international trade and investment increased, the need for reliable and neutral dispute resolution mechanisms led to the rise of arbitral institutions. The institutions have become increasingly important in the global legal landscape.

1 | 💡 Are all institutions the same? Are they all independent and neutral? |

No, they are not identical.

- Different Rules: Each institution has its own set of arbitration rules, timing, and costs.

- Different Services: Some provide more intensive case-management support; others are more “hands-off.”

- Costs Vary: Filing fees and arbitrator hourly rates differ from one institution to another.

Independence and Neutrality

- Designed to Be Neutral: Institutions are meant to be impartial administrators, not favoring either party.

- Institutional Governance: Most have independent councils or boards made up of arbitrators and lawyers from many countries.

- Potential Concerns:

- An institution based in one country may have more local users, leading some to worry about “home-court bias.”

- Funding sources (e.g. member contributions or government ties) can raise questions about true independence.

- Practical Neutrality: In practice, parties pick the institution whose rules, seat, and reputation they trust most. If they doubt neutrality, they can choose a different institution or an ad hoc procedure.

D. Institution’s Power

1. An Institution’s Hard Power

Hard power refers to an institution’s decisive authority in arbitration. This means that the institution has the formal power to make decisions that directly impact the arbitration process. These decisions are typically outlined in the arbitration rules or statutes.

… some decisional authority in order to facilitate an arbitration conducted in accordance with a set of arbitration rules

1 | 💡 What decisional authority? |

Appointment of Arbitrators: The institution can decide who will act as the arbitrators, either based on the rules or laws (statutory).

Procedural Decisions: The institution may make decisions on certain procedural matters like whether a claim is valid (prima facie), whether parties can join a case together (joinder), or whether cases can be consolidated (consolidation).

Scrutiny of Awards: Some institutions review or scrutinize the arbitral awards to ensure they meet certain standards.

Time and Cost Controls: The institution can set procedures to make the arbitration process faster (expedited procedures), or impose caps on the arbitrators’ fees, making the process more efficient and cost-effective.

1 | 💡 What about statutory authority? |

Statutory authority refers to the legal power granted by statutes. For example, in Hong Kong:

Cap. 609, Sections 23 and 24

Section 23 (Article 10 of UNCITRAL Model Law – Number of Arbitrators)

- This section allows the parties to determine the number of arbitrators (usually 1 or 3).

- If the parties cannot agree on the number of arbitrators, the HKIAC (Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre) has the authority to decide on the number of arbitrators (either 1 or 3) in that case.

- Hard power here refers to the institution (HKIAC) having the authority to step in and decide if the parties cannot agree.

Section 24 (Article 11 of UNCITRAL Model Law – Appointment of Arbitrators)

- Article 11 gives the parties the freedom to decide how arbitrators will be appointed.

- If the parties cannot agree on the arbitrators, then the HKIAC has the power to appoint the arbitrators, either directly or by helping the parties reach an agreement.

- In situations where the parties or their appointed arbitrators fail to make the appointments within the required timeframes, the HKIAC can step in and make the appointment. This is another example of the institution exercising its hard power.

- This section outlines the procedure for appointments, including the possibility of a court or other authority stepping in if the institution (or the parties) cannot resolve the issue.

Cap. 609C

Appointment Advisory Board (AAB): This is a 11-member board established by the Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre (HKIAC), with members nominated by prominent organizations such as the Chief Justice and various professional associations.

Consultation: HKIAC must consult at least 3 members of the Appointment Advisory Board before appointing an arbitrator or mediator or deciding on the number of arbitrators. However, the advice is not binding.

Appointment Process: Parties may request the HKIAC to appoint an arbitrator (under section 24 of the Arbitration Ordinance) or mediator (under section 32(1)) by submitting specific forms. The HKIAC will appoint based on factors like the nature of the dispute and availability of qualified persons.

Fee: The standard fee for the appointment of an arbitrator or mediator is HK$8,000, but this may vary depending on the specifics of the case. The HKIAC also has the authority to waive or vary these fees.

Decision on Number of Arbitrators: If the parties cannot agree on the number of arbitrators, the HKIAC decides whether there should be 1 or 3 arbitrators, considering factors like the complexity of the case, the amount in dispute, and customs of the relevant industry.

2. An Institutions’ Soft Power

Soft power refers to a form of influence or persuasion that does not rely on coercion or force but instead uses attraction, appeal, and subtle influence. In the context of arbitration, an institution’s soft power is its ability to shape the arbitration process and the legal landscape through its authority, rules, and practices, without direct imposition or enforcement.

… some decisional authority in order to facilitate an arbitration conducted in accordance with a set of arbitration rules

1 | 💡 What do we mean by soft power? |

In the context of institutions, soft power is the ability to influence or guide the development of international arbitration practices through subtle and non-coercive means, such as:

- Influencing Arbitration Rules and Practices: Institutions, such as the ICC, LCIA, or HKIAC, can introduce or amend arbitration rules to reflect evolving global standards, societal values, and fairness principles. This is done without imposing them through state-enforced laws.

- Appointment of Arbitrators: Institutions exercise soft power by playing a role in the appointment of arbitrators, ensuring diverse, qualified, and impartial individuals are selected. This process can shape the diversity of arbitrators and how they interpret and apply arbitration rules. Institutions influence the broader cultural and social dimension of arbitration through such decisions.

1 | 💡 How do institutions influence change? |

Several initiatives and pledges demonstrate how arbitration institutions use their soft power to influence change, such as:

The Equal Representation in Arbitration Pledge:

This pledge encourages institutions to promote gender equality and diversity in the appointment of arbitrators. By making this pledge, institutions exert soft power to challenge biases and encourage diversity in the arbitration process.

Green Arbitration Pledge:

The Green Arbitration Pledge encourages arbitration participants and institutions to reduce the environmental impact of arbitration proceedings. This includes practices like reducing travel-related emissions and using more sustainable resources. Institutions adopting this pledge influence the arbitration process in an environmentally-conscious direction, leveraging their authority to promote ecological responsibility.

Mindful Business Charter:

This is a set of principles for ethical business conduct, and when institutions endorse it, they promote mindfulness, ethical practices, and inclusivity in arbitration proceedings. This soft power helps embed values such as fairness and transparency in arbitration.

1 | 💡 Should there be limits on that influence? |

Yes, some argue that arbitration institutions should focus primarily on ensuring procedural fairness, efficiency, and impartiality in the arbitration process, without being overly involved in social or political issues. The potential risk is that institutions may impose values that some parties might not agree with, potentially influencing the neutrality of the arbitration process.

However, others argue that these values are part of the evolution of international arbitration and reflect society’s changing expectations. Institutions adopting these soft power strategies may help promote diversity, sustainability, and ethical practices, which are increasingly seen as necessary in modern arbitration.

1 | 💡 Are institutions instruments for social change? |

Arbitration institutions can indeed be seen as instruments for social change. By endorsing various pledges, initiatives, and practices that focus on diversity, sustainability, and ethical conduct, they shape the evolving norms of the arbitration world. This influence extends beyond merely resolving disputes, as institutions help shape the ethical, social, and environmental standards of the arbitration community.

III. Practising Arbitration in a Globalised World

A. International Commercial Arbitration

1. Definition

International commercial arbitration is a means to resolve business disputes between profit-making enterprises.

2. What do Companies / Users say about Arbitration?

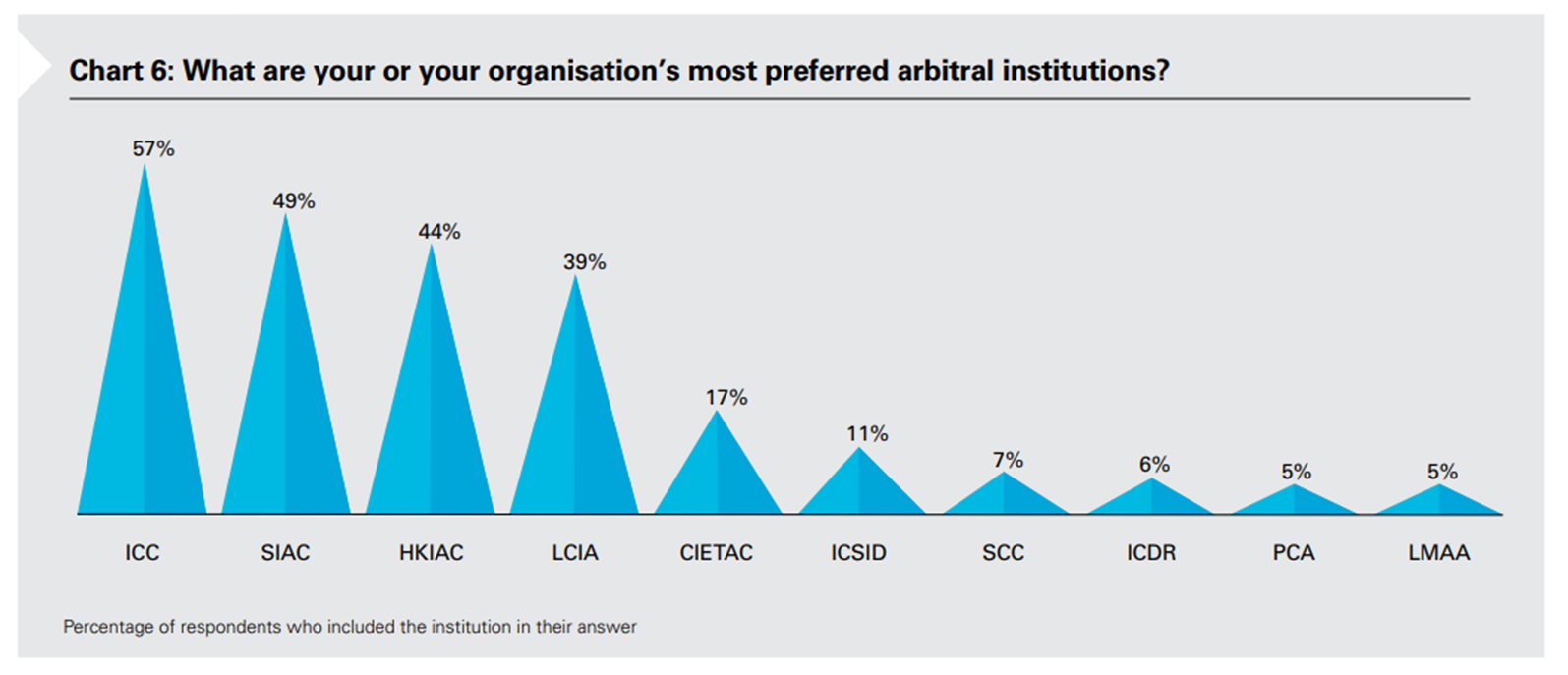

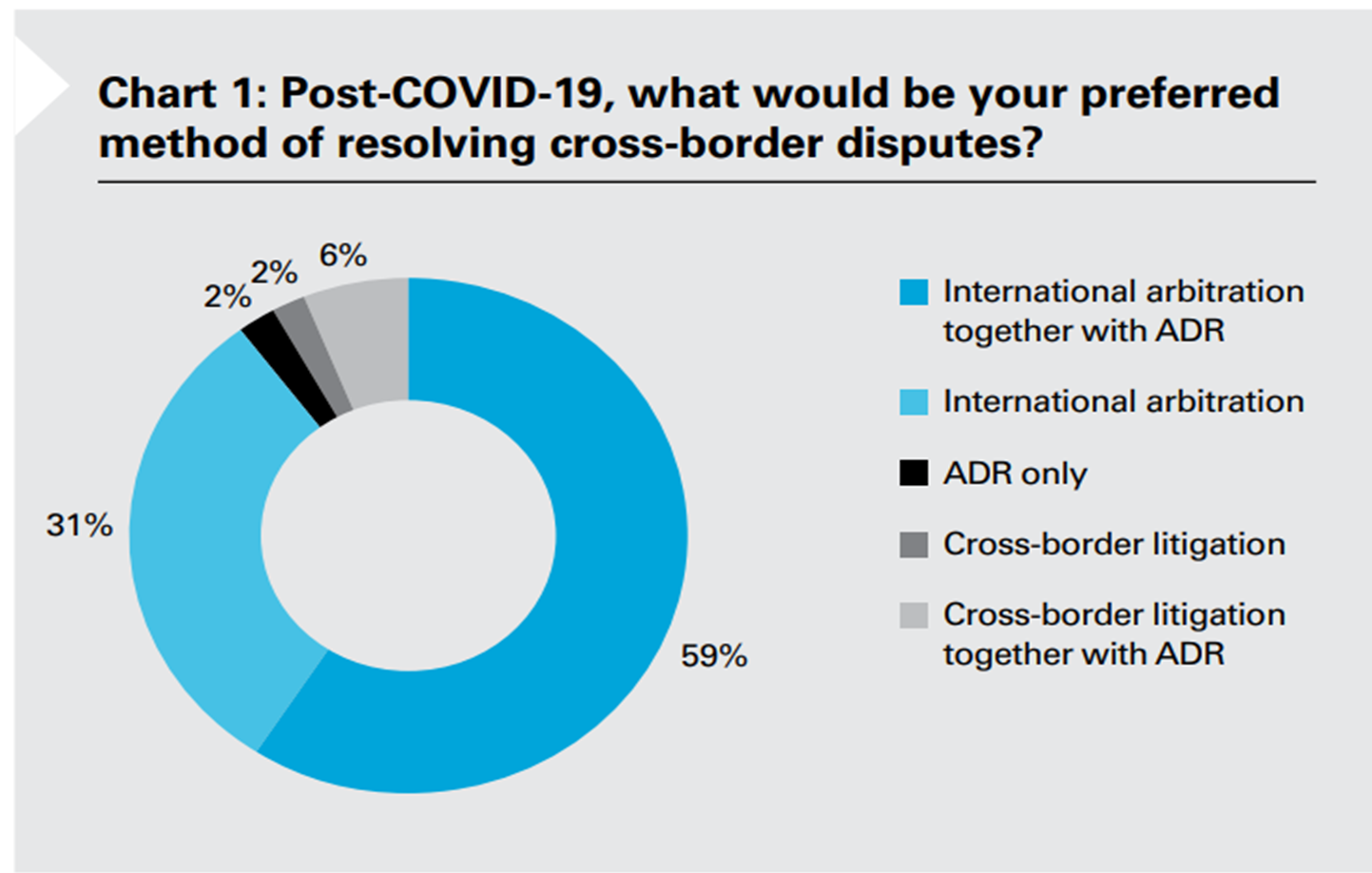

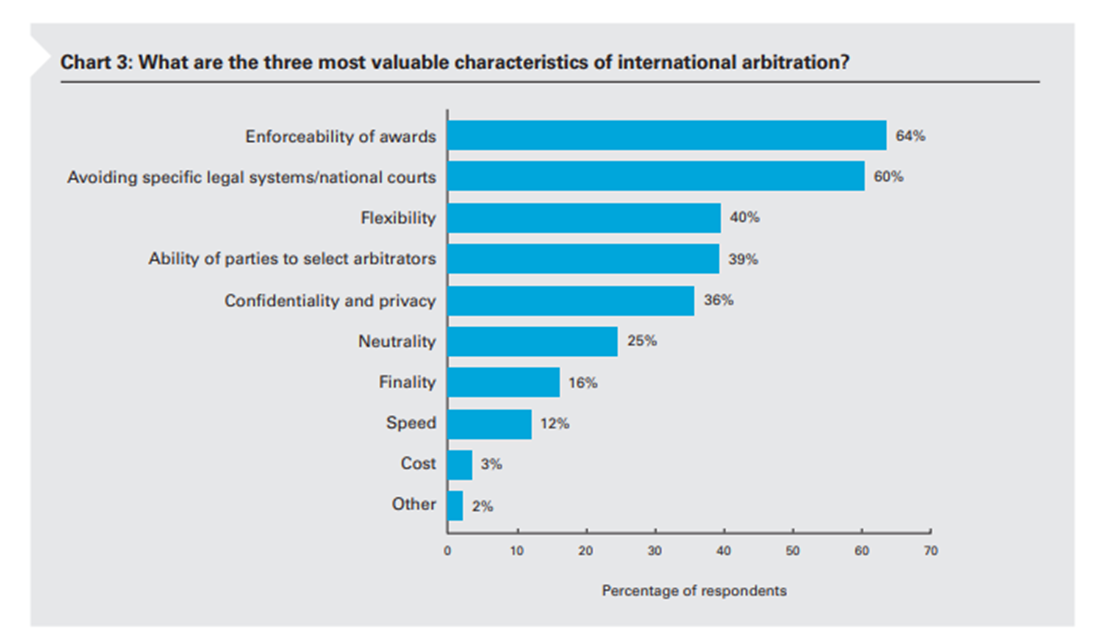

The five most preferred seats for arbitration are: London, Singapore, Hong Kong, Paris and Geneva.

The five most preferred arbitral institutions are: ICC, SIAC, HKIAC, LCIA and CIETAC.

In a Queen Mary University study on energy arbitration (published Jan 2023), results were similar:

- 72% of the respondents gave arbitration a score of 4/5 for suitability as a dispute resolution mechanism ranking much higher than any other form of dispute resolution.

- Neutrality (63%), choice of arbitrators / technical expertise (60%) and enforceability of awards (60%) were seen as main benefits.

- London and Singapore were named as preferred seats.

3. International Commercial Arbitration vs Cross Border Litigation

Concerns re Cross Border Litigation | International Arbitration |

|---|---|

Neutrality of local courts | Arbitrators with neutral nationalities |

Lack of expertise / familiarity with international commercial practices and/or very technical disputes | Technical experts / senior commercial arbitrators to be selected as arbitrators |

Costs and delay | Freedom to adopt specific procedural restraints to limit time / costs |

Lack of convenience | Flexible venue / broad adoption of online hearings |

Jurisdictional issues / forum selection | Very limited grounds for local courts to interfere with jurisdiction of arbitral tribunals |

Enforceability of judgments | Awards broadly enforceable due to New York Convention |

4. Fact of Fiction?

1 | 💡 Is arbitration flexible? |

Arbitration is typically more flexible than litigation. This flexibility is one of its key advantages. Parties can:

- Choose their own arbitrators, subject to institutional rules or mutual agreement.

- Tailor the procedural rules to suit the specific needs of their dispute, as long as these procedures are compatible with the relevant arbitration rules.

- Select the venue (or “seat”) of arbitration, which can influence the applicable legal framework.

This flexibility allows parties to design a process that is more efficient and suited to their specific needs, which is harder to achieve in court proceedings, where procedures are largely standardized and controlled by the court system.

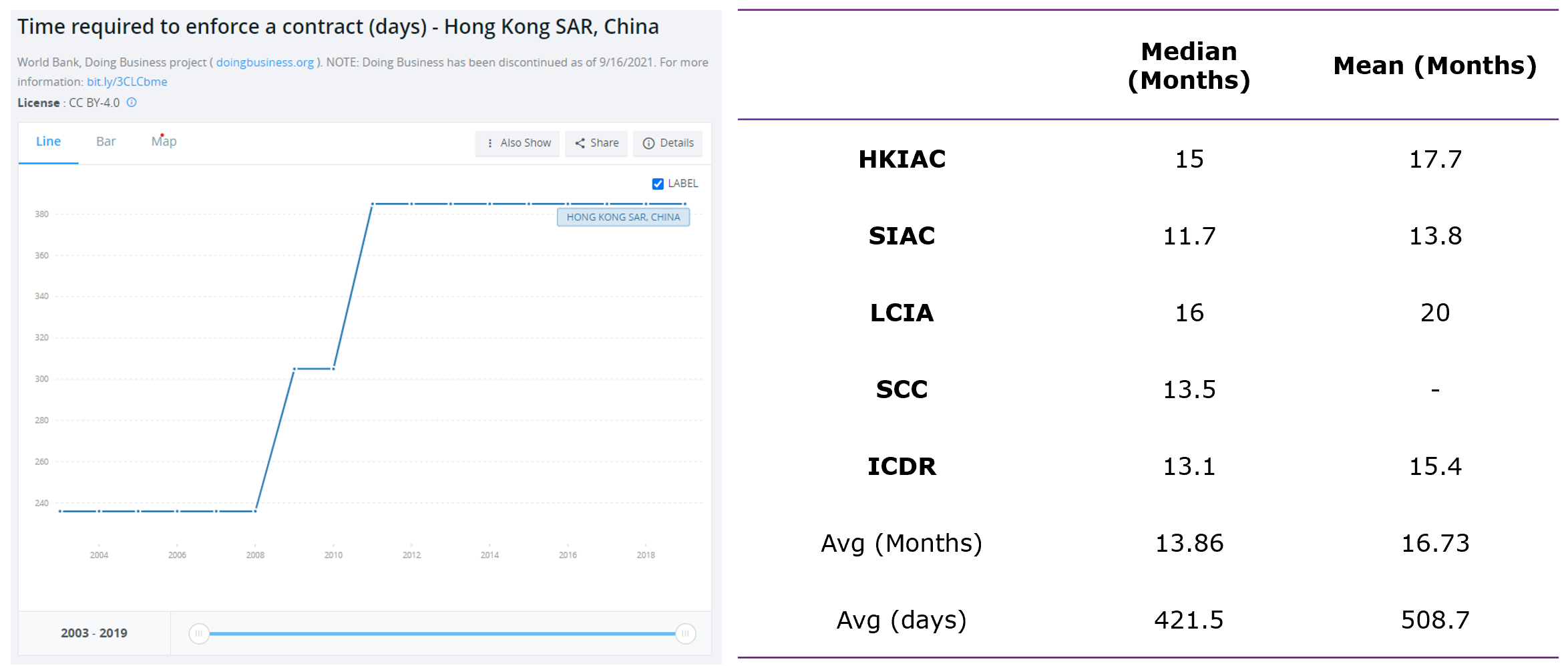

1 | 💡 Is arbitration cheaper and quicker than litigation? |

Arbitration is often cheaper and quicker than litigation, but this is not always the case. Here’s why:

Cheaper:

Arbitration can be more cost-effective because parties have greater control over the proceedings (e.g., fewer procedural delays). Moreover, arbitration avoids the extensive costs associated with public court procedures, like lengthy trials and extensive discovery processes.

Quicker:

Arbitration can be faster due to its streamlined procedures, limited opportunities for appeal, and flexible scheduling. However, delays may still occur depending on the complexity of the case, the efficiency of the arbitrators, or the availability of witnesses and experts.

1 | 💡 Arbitrators better suited to deal with international / highly technical disputes? |

Arbitrators can often be better suited to handle international or highly technical disputes for the following reasons:

Expertise:

Arbitrators are often selected for their specialized knowledge in a particular field, such as construction, technology, or intellectual property, which makes them well-equipped to handle complex and technical matters.

International Scope:

In international disputes, arbitrators are usually well-versed in cross-border legal issues, cultural differences, and international law, which makes them better suited than judges in a national court who might not have this expertise.

1 | 💡 Is arbitration more convenient? |

Arbitration can indeed be more convenient, but it depends on the procedure adopted by the parties:

Convenience:

Arbitration allows the parties to choose the time, place, and manner of the proceedings, which can make it more convenient than court proceedings, especially in international disputes where courts may be located in different jurisdictions.

Depends on Parties’ Choices:

If the parties agree on a streamlined process and an efficient arbitrator, arbitration can be very convenient. However, if the process is poorly designed or if there are significant delays in appointing arbitrators or securing documents, it can become less convenient.

1 | 💡 Is arbitration greener? |

Arbitration can be greener, but it requires party commitment to adopt relevant procedures:

Sustainability:

Arbitration can be made more environmentally friendly by reducing the need for travel (via virtual hearings), minimizing paper use (through electronic submissions), and adopting more sustainable venues and logistics. Some arbitration institutions and parties are increasingly adopting “green” initiatives to reduce the environmental impact of proceedings.

Commitment from Parties:

While arbitration offers the potential for more eco-friendly practices, this depends on the parties’ willingness to adopt them. For example, if the parties insist on in-person hearings or refuse to go paperless, the environmental impact may still be significant.

B. Strategy in Cross Border Disputes

Important points to consider to identify the most appropriate dispute resolution mechanism:

- What are the available counterparties?

- Where are the assets of such counterparties located?

- What is the value of the contract / dispute?

- How / where would a potential award / judgment have to be enforced?

- Availability of interim relief?

At the time when a dispute arises, the options are usually limited and depend on the relevant dispute resolution / arbitration clause in the contract.

It is therefore important to consider these issues before or at the time a contract is entered into between the parties.

C. Case Study

Example 1: Investment Dispute Resolution via Arbitration

This case highlights how arbitration can be used as a mechanism to resolve disputes in complex international investment situations. Let’s break it down step by step:

(1) The Dispute Overview:

Parties Involved:

- Client (Offshore Holdco), with a Hong Kong-listed company (HK Listco) and main operations in the PRC (People’s Republic of China).

- Counterparty, with a similar structure (offshore Holdco and PRC operations).

Investment Structure:

The parties jointly invested in a target company through a Share Purchase Agreement (SPA), with the ultimate goal of listing the target company on the stock exchange. The client secured a put option, allowing them to withdraw from the investment after a set period if the listing did not happen.

Dispute Trigger:

The target company did not list as planned. Consequently, the client wanted to exercise the put option to exit the investment, but the dispute arose regarding how to unwind or end the investment.

(2) Difficulties in Resolving the Dispute:

Offshore Holdcos with No Direct Assets:

The contracting parties (client and counterparty) were offshore Holdcos (holding companies), meaning they did not have direct assets. This made it difficult to enforce any claims directly against them, as they were essentially shell companies with no significant tangible assets.

Assets Located in PRC:

The real assets were held by the parent company of the Holdcos, based in the PRC. The issue here was that the offshore Holdcos did not have direct access to or control over these assets, making the dispute more complicated to resolve.

Incompatible Arbitration Clauses:

The arbitration clauses in the various agreements (SPA, guarantee agreement, etc.) were not compatible, meaning the different agreements could not be consolidated into a single arbitration proceeding. This posed a logistical challenge in terms of trying to resolve all issues in one place, as the arbitration rules would differ.

(3) The Solution

To overcome these challenges, the legal team used the following approach:

Commence HKIAC Arbitration under a Guarantee Agreement:

The arbitration was initiated through the Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre (HKIAC) under the guarantee agreement. Importantly, this agreement involved the PRC-based parent companies, who had assets within China. By focusing on the guarantee provided by the parent companies, they were able to bring the dispute into the scope of arbitration, even though the main contracting parties were offshore entities.

Use of Interim Relief to Freeze Assets in the PRC:

A key strategy was to request interim relief in the form of freezing the assets in the PRC. This allowed the parties to effectively secure the value of the dispute by freezing assets in excess of RMB 550 million. This step was crucial because it gave the client leverage in the negotiations and ensured that the assets were protected while the dispute was being resolved.

Negotiation Pressure:

With over RMB 550 million in assets frozen, the pressure on the parties significantly increased. As a result, both parties were compelled to return to the negotiation table to seek a settlement, as the frozen assets made it clear that the status quo could not continue indefinitely.

(4) Outcome

- The interim relief (asset freeze) was successful in forcing the parties to negotiate and reach a resolution. The threat of losing access to valuable assets in the PRC created sufficient pressure for both sides to find common ground.

- Arbitration provided a structured, neutral platform to address the dispute, with the option for interim measures to protect the client’s position while the dispute was resolved.

Key Takeaways:

- Arbitration for Offshore Parties: Even when the parties involved are offshore entities without direct assets, arbitration can still be a useful tool, particularly if the dispute involves guarantees or assets located in a jurisdiction where interim measures are possible.

- Interim Relief in Arbitration: The ability to obtain interim relief to freeze assets (especially in the PRC, where enforcement can be challenging) plays a critical role in influencing the outcome of the dispute. This can provide a tactical advantage, forcing parties to negotiate.

- Arbitration Clauses and Consolidation: If arbitration clauses are incompatible across multiple agreements, it may be necessary to find creative solutions, such as focusing on the guarantee agreement or a specific clause that permits arbitration.

In this case, arbitration served as a powerful mechanism not only for resolving the dispute but also for exerting pressure on the counterparty to come to the table for negotiations.

Example 2: Enforcing an Arbitration Award in a Complex International Dispute

This case presents another scenario in which a large multinational company (the client) sought to enforce an arbitration award in a dispute involving mismanagement and embezzlement of assets. Let’s break down the case details:

(1) The Dispute Overview

- Parties Involved:

- Client: A large multinational corporation that had invested in an offshore company. The client had shares in the Hong Kong-listed company (HK Listco), which owned subsidiaries operating in the PRC.

- Counterparty: Allegedly mismanaged the target company and embezzled assets.

- The Investment:

The client invested in an offshore company with key operating subsidiaries in the PRC. However, after discovering that the counterparty had mismanaged the company and embezzled funds, a dispute arose. - The Arbitration: The client engaged a Singapore-based law firm to pursue the dispute, leading to a successful SIAC (Singapore International Arbitration Centre) award. The arbitration awarded in the client’s favor, but enforcement became problematic, as the client did not engage a Hong Kong/China law firm until several years after the arbitration, during the enforcement phase.

(2) Difficulties Encountered

No Asset Searches During Arbitration:

One of the major issues was that no contemporaneous asset searches were conducted during the ongoing arbitration. Typically, asset searches can help identify available assets for enforcement purposes, but in this case, it was not done early on.

Parallel Structure Setup by Counterparty:

While the arbitration was ongoing, the counterparty set up a parallel structure in the PRC. This structure was used to transfer key assets, including key employees, away from the original target company. As a result, the target company (the one involved in the dispute) lost its assets, and the remaining PRC structure became an empty shell with no substantial value.

Empty Shell at Time of Award:

By the time the arbitration award was issued, the remaining structure of the company in the PRC had been hollowed out. There were no valuable assets remaining that could be used for enforcing the award, which made the enforcement process incredibly difficult.

(3) The Solution and Steps Taken

Realization of Asset Shift and Lack of Enforceable Assets:

Since the asset shift to the parallel structure had gone unnoticed during the arbitration, there were no remaining assets in the target company that could be used to enforce the arbitration award.

Criminal Complaint and Blacklisting:

To take action against the counterparty, a criminal complaint was filed in the PRC, targeting the involved director/shareholder. Additionally, a blacklisting process was initiated in China to prevent the involved parties from engaging in certain business activities. This was a strategy to put pressure on the counterparty, even if it did not directly recover assets.

Appointment of Liquidators:

To access books and records and trace the dispersed assets, liquidators were appointed both offshore and in Hong Kong. Their role was to dig deeper into the structure and financials of the offshore company and its PRC subsidiaries to try to locate the hidden assets and understand the full scale of the asset transfers.

Costly Asset Searches and Investigations:

As the assets were not easy to trace, costly and extensive asset searches and investigations were initiated. However, these processes were resource-intensive and uncertain. The investigation was unclear in terms of whether it would lead to meaningful recovery of the misappropriated funds or assets.

(4) Challenges with Recovery

The primary issue here was that while the SIAC award was in favor of the client, the counterparty had already transferred assets to a parallel structure, and those assets were not easily traceable. Additionally, by the time enforcement efforts were initiated, much of the PRC structure had become an empty shell, rendering enforcement difficult.

The asset searches were costly and time-consuming, and it was not immediately clear if the client would be able to recover any significant amount. The criminal complaint and blacklisting were strategic steps to apply pressure on the counterparty, but these actions alone could not ensure a meaningful recovery.

Key Takeaways

Importance of Asset Searches Early On:

One of the key lessons here is the importance of conducting asset searches during the arbitration process itself. This would have allowed the client to identify available assets to target for enforcement before the counterparty moved them.

Parallel Structures and Asset Concealment:

The case underscores how parallel structures (especially in jurisdictions like the PRC) can be used to shield assets from enforcement. This strategy makes it harder for the winning party to recover any funds, even when the award is in their favor.

Post-Award Enforcement Challenges:

The case illustrates that even after obtaining a favorable arbitration award, the enforcement phase can be extremely complex and costly, especially when the counterparty is actively trying to hide or transfer assets to another jurisdiction.

Use of Liquidators and Investigators:

The appointment of liquidators and the reliance on asset tracing experts are essential in international disputes where assets are hidden or transferred to avoid enforcement. However, these measures can be time-consuming and expensive with no guaranteed success.

In essence, this case highlights the challenges involved in enforcing an arbitration award when the counterparty has taken steps to hide or transfer assets, and it shows how the client was forced to pursue costly and complicated enforcement measures.

Class 2 - Discovery and Disclosure of Documents in International Arbitration

I. Introduction

1 | 💡 What is discovery / document production? |

Discovery is a term usually used in common law countries to identify a process by which, commonly before the hearing / trial, evidence can be obtained.

The available tools to obtain evidence through discovery include:

- Requests for document production

- Interrogatories

- Inspection of documents, goods, etc.

- Requests for a person to be provided as a witness

In civil procedures, parties can apply to the court’s assisting in collecting documents from counter-parties and non-parties. They are ways to collect evidence too, but strictly speaking not the “discovery / document production” process in common law proceedings.

In arbitration, discovery of documents is called document production and is not automatic / mandatory as in litigation (under common law).

II. Discovery in Hong Kong Litigation

After the close of pleadings, discovery by the parties of the documents “which are or have been in their possession, custody or power relating to matters in question in the action.” (O.24, r.1, RHC Cap. 4A)

- Possession, custody, or power: including documents of other parties.

Any document which, it is reasonable to suppose, “contains information which may enable the party (applying for discovery) either to advance his own case or to damage that of his adversary, if it is a document which may fairly lead him to a train of inquiry which may have either of these two consequences” must be disclosed. (Compagnie Financière du Pacifique v. Peruvian Guano Co. (1882) 11 Q.B.D. 55)

Discovery by exchanging lists of documents within 14 days after close of pleading. (O.24, r.2)

To ensure completeness, the court can:

- order a party to provide a sworn affirmation verifying its list of documents, i.e. to confirm that the party has disclosed all relevant documents in his possession, custody and control.(O.24, r.3)

- order discovery of a specific document or class of documents.(O.24. r.7)

Parties need to make the documents available for inspection.(O.24, r.9)

III. Applicable rules for document disclosure in international arbitration

A. Key Sources

1 | 💡 Where to find the relevant rules on document production / use of evidence in international arbitration? |

Parties can refer to the rules on evidence / document disclosure in the arbitration agreement. Tribunals can make procedural orders that incorporate / adopt the relevant rules as guidelines for the ongoing arbitration.

Below is an extract from a procedural order in an arbitration:

DOCUMENTARY EVIDENCE

The Parties and the Tribunal may, in all matters pertaining to evidence, be guided but not bound by, the IBA Rules on the Taking of Evidence in International Arbitration.

The Parties shall identify all relevant documents in their submissions…

Either Party may request, and the Tribunal may direct, the other Party or Parties to produce any relevant documentary evidence in its or their respective possession, custody or control. Any documents which the Tribunal orders to be produced shall be transmitted to the Tribunal within any time limit directed by the Tribunal…

All documents submitted by the Parties shall be accepted as being true copies of the originals unless their authenticity is expressly challenged by the other Party.

B. National Laws

The relevant local law in Hong Kong is the Arbitration Ordinance (Cap. 609) which, as with local laws in many other countries, adopts / incorporates the UNCITRAL Model Law.

Section 47 (2)

If or to the extent that there is no such agreement of the parties, the arbitral tribunal may, subject to the provisions of this Ordinance, conduct the arbitration in the manner that it considers appropriate.

Section 47 (3)

When conducting arbitral proceedings, an arbitral tribunal is not bound by the rules of evidence and may receive any evidence that it considers relevant to the arbitral proceedings, but it must give the weight that it considers appropriate to the evidence adduced in the arbitral proceedings.

Section 56 (1)

Unless otherwise agreed by the parties, when conducting arbitral proceedings, an arbitral tribunal may make an order […]

(b) directing the discovery of documents or the delivery of interrogatories;

(c) directing evidence to be given by affidavit; or

(d) in relation to any relevant property

Other relevant local laws are:

Arbitration Law of the People’s Republic of China

- Article 43 Parties shall provide the evidence in support of their own arguments. The arbitral tribunal may, as it considers necessary, collect evidence on its own.

- Article 45 The evidence shall be presented during the hearings and may be examined by the parties.

- Article 46 Under circumstances where the evidence may be destroyed or lost or difficult to obtain at a later time, a party may apply for preservation of the evidence. If a party applies for preservation of the evidence, the arbitration commission shall submit his application to the basic people’s court in the place where the evidence is located.

The arbitral tribunal may, as it considers necessary, collect evidence on its own.

International Arbitration Act (Cap. 143A) (IAA) [Singapore]

Arbitration Act 1996 [England, Wales, Northern Ireland]

International Arbitration Act 1974 (IAA) [Australia]

C. Arbitral Institutions

Institutional rules deal with document production and feature frequently in international arbitration (as they are usually incorporated in the Parties’ arbitration agreement).

- HKIAC Administered Arbitration Rules (2024)

- ICC Arbitration Rules (2021)

- UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules (2013)

- SIAC, LCIA, various others…

1. HKIAC Administered Arbitration Rules (2024)

Scope for document production narrower than for HK court proceedings.

Art. 22.3

At any time during the arbitration, the arbitral tribunal may allow or require a party to produce documents, exhibits or other evidence that the arbitral tribunal determines to be relevant to the case and material to its outcome. The arbitral tribunal shall have the power to admit or exclude any documents, exhibits or other evidence.

Art. 13.1

[…] the arbitral tribunal shall adopt suitable procedures for the conduct of the arbitration in order to avoid unnecessary delay or expense, having regard to the complexity of the issues, the amount in dispute and the effective use of technology, and provided that such procedures ensure equal treatment of the parties and afford the parties a reasonable opportunity to present their case.

2. ICC Arbitration Rules

The tribunal is not expressly empowered to order document disclosure, but authority is implied.

Article 25(1) (2021 Rules)

[t]he Arbitral Tribunal shall proceed within as short a time as possible to establish the facts of the case by all appropriate means,

Article 25(5)

may summon any party to provide additional evidence.

D. International Guidelines

Guidance is also found in guidelines published by international organizations which can be incorporated into arbitral proceedings:

- IBA Rules on the Taking of Evidence in International Arbitration (IBA Rules)

- Inquisitorial Rules on the Taking of Evidence in International Arbitration (The Prague Rules)

- ICC Arbitration Commission Report on Managing E-Document Production

- CIArb Protocol for E-disclosure in Arbitration

1. IBA Rules

IBA Rules are widely accepted as internationally applicable standards / best practices on taking evidence (including document production) in international arbitration.

- A balanced approach taken between civil and common law procedures.

- Scope of production: a document request has to be:

- for specific documents or for specific and narrow categories of documents [3(3)(a)(ii)]

- prima facie relevant to the case and material to its outcome [3(3)(b)]

- for documents

- not in the possession, custody or control of the requesting party [3(3)(c)(i)],

- in the possession, custody or control of the requested party (Article 3(3)(c)(ii)

- not unreasonably burdensome to produce [3(3)(c)(i)]

Article 9 of the IBA Rules

- The Arbitral Tribunal shall determine the admissibility, relevance, materiality and weight of evidence.

- The Arbitral Tribunal shall, at the request of a Party or on its own motion, exclude from evidence or production any Document […] for any of the following reasons:

- lack of sufficient relevance to the case or materiality to its outcome;

- legal impediment or privilege under the legal or ethical rules determined by the Arbitral Tribunal to be applicable…;

- unreasonable burden to produce the requested evidence;

- loss or destruction of the Document that has been shown with reasonable likelihood to have occurred;

- grounds of commercial or technical confidentiality that the Arbitral Tribunal determines to be compelling;

- grounds of special political or institutional sensitivity […]; or

- considerations of procedural economy, proportionality, fairness or equality […].

- The Arbitral Tribunal may, at the request of a Party or on its own motion, exclude evidence obtained illegally.

2. Competitor to IBA Rules: Prague Rules

The Prague Rules came into effect on 14 December 2018. The working group creating the Prague Rules comprises mostly of civil law practitioners and the civil law influence is reflected in the Prague Rules.

The Prague Rules are aimed at increasing efficiency of arbitration by encouraging a more active role for arbitral tribunals in managing proceedings (as with courts in civil law countries).

Document production is discouraged and the Prague Rules require the tribunal to decide at the outset whether document production is necessary. In case the tribunal allows for production, requests have to pertain to specific document relevant and material to the outcome of the case.

IV. Comparison of litigation and arbitration

International Arbitration | Court / Litigation | |

|---|---|---|

Discovery automatic | No automatic right to request disclosure – depending on discretion of tribunal | Automatic process for actions commenced by writ [HK – common vs civil law] |

Counterparties for | Limited to parties in arbitration | Parties to dispute / third parties |

Scope | No common standard but generally less broad - relevant and material to a party’s case (IBA Rules) | Wide scope: relevant document under Peruvian Guano[HK – common vs civil law] |

Privilege protection | Yes | Yes [HK – common vs civil law] |

Confidentiality | Yes | Implied but otherwise specific court order required |

Characteristics |

|

|

V. Practical application in international arbitration

A. Guidelines for Legal Representatives Regarding Document Production

At the outset of the dispute, inform the client about the importance of preserving potentially relevant documents (continuing duty).

Also, at the outset, clients should locate / search for relevant / material documents as soon as possible (at the direction or with the assistance of the legal representative).

At an early stage of the arbitration, consider and agree applicable rules and scope of documents disclosure – whether to exclude or limit the scope of document requests, providing time for document requests and disclosure in the timetable.

During dispute, document requests (or objections to such request) should only be made for a proper purpose (and not for procedural advantage e.g. to create delay).

If production of documents is agreed by the parties or ordered by the tribunal, parties are required to abide by such agreement or orders (and do not unreasonably withhold relevant documents).

During dispute, advise client on issues such as privilege, data privacy, state secrets etc. which may affect document production.

B. Disclosure and Inspection of Documents in Arbitration Proceedings

Each party would normally produce with its submissions, witness statements and expert reports, documents in support of its propositions and facts presented therein.

Additional / specific production of documents would then only be required to obtain documents going beyond what was already produced by each party with submissions – i.e. if more documents exist that are relevant / material to the issues in the dispute.

As discussed, unless specifically provided for in the parties’ arbitration agreement, the tribunal would usually make orders at the outset of the arbitration how such document requests should be formulated and the process and timing for the same.

Here is an example from a Procedural Order given by a tribunal:

Disclosure of documents

- Disclosure or discovery of documents shall be carried out with the IBA Rules serving as a guideline.

- Any requests for disclosure of documents shall be in accordance with the procedural timetable and in the form of a Redfern schedule.

[…]- No new evidence may be submitted in the agreed hearing bundle unless agreed between the parties or permitted by the Tribunal.

C. Reasons for Objecting to Document Requests

- Failure to identify document/category of document with sufficient detail.

- Documents identified lack sufficient relevance or materiality.

- Documents cannot be produced due to:

- Privilege.

- Confidentiality.

- State secret / data privacy, other legal grounds.

- Contractual or other grounds.

- Production of documents would be an unreasonable burden.

- Loss or destruction.

- Considerations of procedural economy, proportionality, fairness or equality.

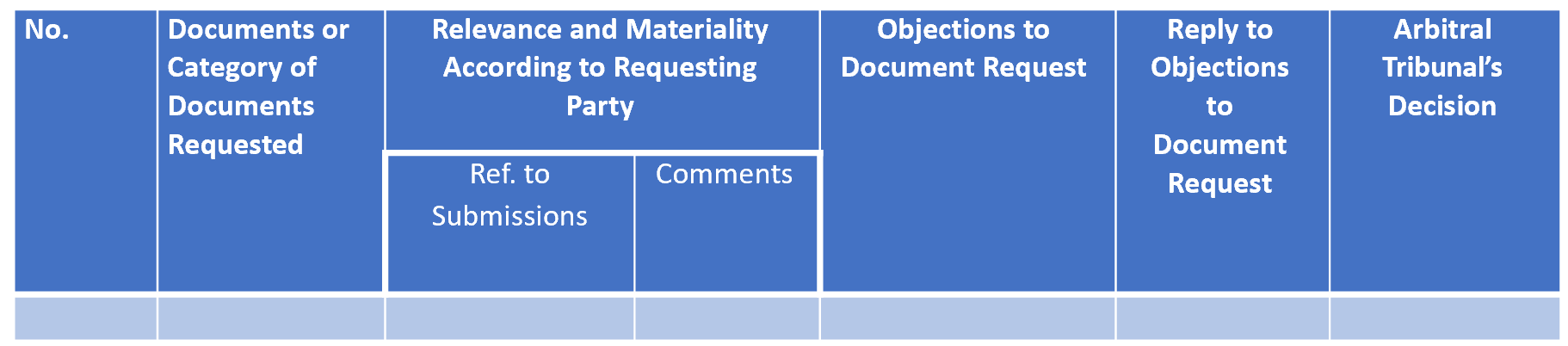

D. Redfern Schedule

1. Introduction

If parties cannot agree document requests, the tribunal will usually ask for the preparation of a joint document with requests from both sides, which allows the tribunal to rule on each request.

An example of such a document is the so-called Redfern Schedule – a schedule for document production popularized by Alan Redfern.

2. Basic Checklist for Redfern Schedule

Check which rules apply, and the procedural order for Tribunal’s directions on document disclosure. | |

CATEGORISE the different claims, counterclaims, or defence. | |

DESCRIBE requested category of document with SPECIFICITY (sufficient details to identify it) [IBA, Art. 3(a)(i) and (ii)] E.g.: “[Document category, e-mails, reports, agreements] in relation to, or pertaining to [specific topic] involving [specific entities or persons] from [date]” | |

3.1. | Name or nature of the document (e.g. mandate, e-mail, agreement) |

3.2. | Identify specific date range for requested document(s) |

3.3. | Set out individuals or entities who created, are mentioned, or somehow related to, involved with the document. |

3.4. | For e-mails, provide search keywords (e.g. “operating agreement negotiation”) |

3.5. | “Documents reasonably believed to exist” – be prepared to justify this (by inference, implication). |

EXPLAIN document’s MATERIALITY and RELEVANCE [IBA, Art. 3(b)] | |

4.1. | Identify the material (sub) issue between the parties that the documents are responsive to. |

4.2. | Explain the relevance of the document to the material (sub) issue between the Parties. |

4.3. | Explain how the documents are relevant to the case and material to its outcome |

4.4. | Provide SPECIFIC REFERENCES and quotes in the pleadings to guide the Tribunal. |

EXPLAIN why the documents requested are in the CUSTODY, POSSESSION, or CONTROL of the other party, and it is NOT UNREASONABLY BURDENSOME TO PRODUCE [IBA, Art.3(c)(i)(ii)]. | |

[For Opposing Party] OBJECT to document based on: | |

6.1. | Or, other grounds including: |

3. Real example of Redfern Schedule (anonymized)

Oil & gas dispute in relation to a gas field development project

No. | Documents or Category of Documents Requested | Relevance and Materiality According to Requesting Party | Objections to Document Request | Reply to Objections to Document Request | Arbitral Tribunal’s Decision | |

Ref. to | Comments | |||||

1. | The original mandate and/or instructions and/or service agreement agreed between Dept. A and Dept. B, including a description of scope of work and responsibilities, budget, and schedule between 2010 and 2020. | Statement of Defence (SOD) / para. 125 | It is a material issue between the Parties whether Rs complied with its obligations with respect to Project management under the Operating Agreement, which required Dept. B to report to Dept. A. | Respondents object to this request. | The Respondents do not contest that the relevant mandate and service agreements exist and can be produced without undue burden. They only take issue with the meaning of the word “instructions”. | The Request is granted |

2. | The studies and reports (and all underlying data relied on) relating to the Respondents’ attempted exploration and development of the gas field. | SOD/ 450 | It is a material issue between the Parties whether the Respondents failed to appraise the gas field and drill for additional gas. | Respondents object to this request. | Response required additional submissions to the tribunal on state secretbut the core points made were:

| The Request is granted. |

No. | Documents or Category of Documents Requested | Relevance and Materiality According to Requesting Party | Objections to Document Request | Reply to Objections to Document Request | Arbitral Tribunal’s Decision | |

Ref. to | Comments | |||||

1. | Documents generated internally by the Claimants discussing or referring to its decision to purchase Microsoft software licenses in the amount of USD 150,000 including communications, internal studies or surveys, reports and other documents regarding the Claimant’s alleged finding and purchase. | SOC / 359 | These documents should be in the Claimant’s possession or control as are Claimant’s internal documents. | Claimant will search for and produce non-privileged Documents in its possession, custody or control that are responsive to this request. | The Claimant’s position is noted, without prejudice to the generality of the Respondents’ Request as originally formulated. | It is noted that Claimant agrees to search for and produce non-privileged Documents. No further order is made. |

F. HKIAC 2024 Administered Arbitration Rules

Apart from other changes, the 2024 Rules include two additions which are relevant in terms of the Tribunal’s decision on document production:

- The Rules require the Tribunal to take into account the environmental impact of arbitration at the stage of determining procedures for the arbitration but also when ruling on costs (Articles 13.1 and 34.4(f)).

- The Rules encourage party agreement on, and empower the Tribunal to order, measures for the protection of information security in the arbitration (Articles 13.2 and 45A).

G. Other considerations for document production

E-Discovery

- Electronic aspect of identifying, collecting and producing electronically stored information in response to a request for production

- Requests are scoped by:

- Custodians, time period and key words

- Special document review and search platform used for the process

- Potential use of AI in addition to or replacing search algorithms

Green Pledge

- The Campaign for Greener Arbitrations.

- Electronic exchange of documents, no hard copy required.

- Environmental impact as consideration for procedures to be adopted in arbitration under 2024 HKIAC Rules.

Data privacy

- Consent for cross-border transfer of private data.

- Pre-approval required by relevant authorities.

- Ability for tribunal to adopt measures for information security under 2024 HKIAC Rules.

VI. Specific issues

A. Privilege

While authority on privilege is limited in international arbitration, it is universally recognized that privilege protection exists in arbitration.

The IBA Rules protect privilege in the Arts. 9(2)(b) and 9(4). While there are additional types of privilege, the two most relevant types (which are also expressly protected under the IBA Rules) are:

- Legal advice privilege Art. 9(4)(a).

- Without prejudice / settlement negotiation privilege Art. 9(4)(b).

The exact scope of legal advice privilege is defined by national laws and deciding which law applies is a choice of law issue.

Art. 9(4)(c) IBA Rules specifies that the ‘expectations of the Parties and their advisors at the time the legal impediment or privilege is said to have arisen’ should be taken into consideration. This could potentially disadvantage one party where its home jurisdiction does not have laws protecting privilege equivalent to the rules available under common law - Art. 9(4)(e) IBA Rules provide that arbitral tribunals should respect the fairness and equality of the parties when deciding on privilege.

B. Third Party Production

Generally, orders of the tribunal can only bind parties to the arbitration, therefore, third party discovery cannot be ordered by the tribunal.

Under Art. 3(9) of the IBA Rules, the tribunal can take the necessary steps for third party production if it determines that the documents would be relevant and material.

The Arbitration Ordinance provides for third party production:

Section 55(1) [Article 27 of the UNCITRAL Model Law]

The arbitral tribunal or a party with the approval of the arbitral tribunal may request from a competent court of this State assistance in taking evidence. The court may execute the request within its competence and according to its rules on taking evidence.

Section 55(2)

The Court may order a person to attend proceedings before an arbitral tribunal to give evidence or to produce documents or other evidence.

VII. Sanctions

In Hong Kong, under the Arbitration Ordinance (AO), tribunals have the power to make interim decisions to preserve evidence and protect relevant property during the arbitration process.

1. Types of Interim Measures Available

Preservation, custody, or sale of relevant property

The tribunal can order that relevant property (e.g., documents, goods) involved in the arbitration be preserved, stored, or even sold if necessary.

(Sections: 56(1)(d)(i), 56(6), 60(1)(a), 60(2))

Inspection, photographing, preservation, or detention of relevant property

The tribunal can order that property be inspected, photographed, or kept in custody to prevent tampering.

(Sections: 56(1)(d)(i), 56(6), 60(1)(a), 60(2))

Sampling, observation, or experiments on relevant property

The tribunal can order that samples be taken from property, or that experiments or observations be conducted to preserve evidence.

(Sections: 56(1)(d)(ii), 56(6), 60(1)(b), 60(2))

Interim injunctions or other interim measures of protection

The tribunal can issue temporary orders (like injunctions) to protect the parties’ interests until the arbitration is finished.

(Sections: 35, 45)

2. Power of the Tribunal and Courts

- The tribunal has the primary power to make these interim orders.

- However, some interim measures can also be ordered by the courts (e.g., Section 45, 60(1), 60(3), 60(4)).

- Enforcement: Any interim measure made by the tribunal can be enforced by the courts. (Section: 60 AO)

3. Preservation of Evidence under PRC-HK Interim Measures Arrangement

In addition to the AO, the PRC-HK Interim Measures Arrangement also allows for the preservation of evidence in Hong Kong and mainland China, ensuring cooperation between the two jurisdictions.

4. Sanctions for Non-Compliance

The tribunal cannot directly fine or impose coercive sanctions (like contempt) for failure to comply with evidence production orders.

If a party refuses to comply with an order to produce evidence, the tribunal may ask the courts to enforce the order or may draw an adverse inference (negative assumption) about that party’s case.

Example: In the case of Active Media Services Inc v Burmester (2021), the English court drew an adverse inference against the claimant because they deliberately deleted emails just before trial and failed to call important witnesses.

Class 3 - Challenges to Jurisdiction and Tribunals

I. Challenges to Arbitrators

A. Introduction

The focus of arbitration lies in the decision-making process, which is primarily shaped by the arbitrator’s role in guiding various procedural and substantive phases. This class’s discussion explores how decisions are made, the role of arbitrators, the types of awards issued, and other procedural considerations. The objective is to understand how these elements come together to contribute to the arbitration process and build a foundation for effective outcomes.

1. Basic Definition of Arbitration

International commercial arbitration is a means by which international business disputes can be definitively resolved, pursuant to the parties’ agreement, by independent, non-governmental decision-makers, selected by or for the parties, applying neutral adjudicative procedures that provide the parties an opportunity to be heard. —— G. Born, §1.02 International Commercial Arbitration (3rd Edition, 2021)

- Non-governmental decision-maker

- Chosen by or for the parties

- To render a final and binding decision

- Using adjudicatory procedures

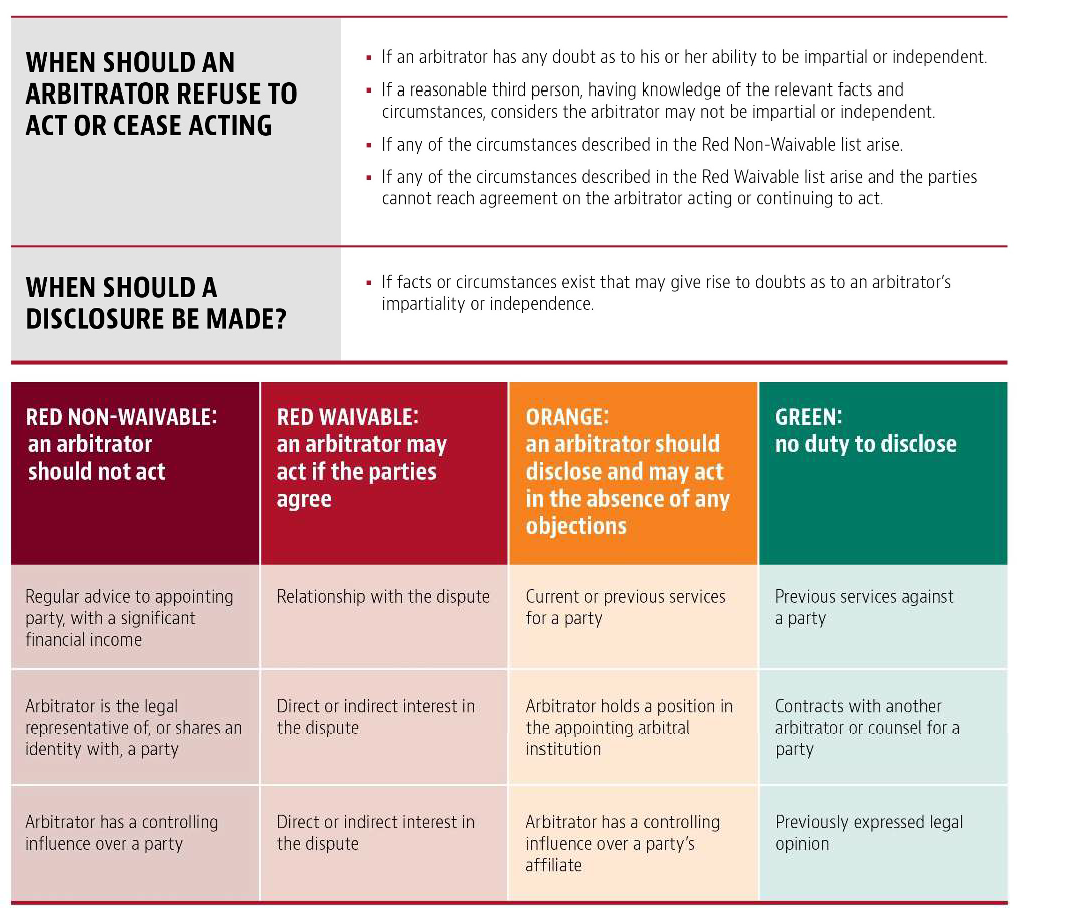

2. Independence v Impartiality

In Hong Kong, both independence and impartiality are required. The independence ensures that an arbitrator’s decision is not influenced by any relationship with one of the parties, while impartiality ensures that the arbitrator has no bias towards one party’s case over the other.

Independence: the existence of a relationship between the arbitrators and one of the parties. Usually capable of objective quantification.

e.g. arbitrator is 30% shareholder in one of the parties

Impartiality: the arbitrator’s state of mind which is more difficult to assess / subjective

e.g. arbitrator actively prefers one party over the other

Not every jurisdiction requires both:

- England: Only impartiality is emphasized under the Arbitration Act 1996 (s. 24(1)(a)), meaning the law focuses on ensuring that an arbitrator does not favor one party over the other.

- USA: Impartiality is the core standard under the Federal Arbitration Act (s. 10(a)(2)), which aims to prevent situations where arbitrators have a personal or financial interest in the outcome of the case.

1 | 💡 Is impartiality sufficient? |

In jurisdictions that only require impartiality (e.g., England, the USA), impartiality might be seen as sufficient because the assumption is that as long as an arbitrator does not consciously favor one party, fairness is ensured.

In jurisdictions like Hong Kong, both independence and impartiality are required because an arbitrator could still act impartially, but any financial or personal relationships could undermine the perceived fairness and integrity of the process.

B. Entitlement to Challenge Arbitrators

1. Legal Basis

① s. 25 Arbitration Ordinance giving effect to Art 12 Model Law

Article 12. Grounds for challenge

When a person is approached in connection with his possible appointment as an arbitrator, he shall disclose any circumstances likely to give rise to justifiable doubts as to his impartiality or independence. An arbitrator, from the time of his appointment and throughout the arbitral proceedings, shall without delay disclose any such circumstances to the parties unless they have already been informed of them by him.

An arbitrator may be challenged only if circumstances exist that give rise to justifiable doubts as to his impartiality or independence, or if he does not possess qualifications agreed to by the parties. A party may challenge an arbitrator appointed by him, or in whose appointment he has participated, only for reasons of which he becomes aware after the appointment has been made.

② s. 26 Arbitration Ordinance giving effect to Art 13 Model Law

Article 13. Challenge procedure

1)The parties are free to agree on a procedure for challenging an arbitrator, subject to the provisions of paragraph (3) of this article.

(2)Failing such agreement, a party who intends to challenge an arbitrator shall, within fifteen days after becoming aware of the constitution of the arbitral tribunal or after becoming aware of any circumstance referred to in article 12(2), send a written statement of the reasons for the challenge to the arbitral tribunal. Unless the challenged arbitrator withdraws from his office or the other party agrees to the challenge, the arbitral tribunal shall decide on the challenge.

If a challenge under any procedure agreed upon by the parties or under the procedure of paragraph (2) of this article is not successful, the challenging party may request, within thirty days after having received notice of the decision rejecting the challenge, the court or other authority specified in article 6 to decide on the challenge, which decision shall be subject to no appeal; while such a request is pending, the arbitral tribunal, including the challenged arbitrator, may continue the arbitral proceedings and make an award.

2. Practical Considerations

1 | 💡 Do the parties have unlimited choice to agree with the challenge procedure? Can they resolve challenges by flipping a coin? |

No, parties do not have unlimited choice when it comes to agreeing on a challenge procedure. While parties have some flexibility in setting procedures within their arbitration agreement, the challenge procedure must be consistent with fundamental principles of fairness and due process.

- Challenge Procedure Constraints: Many arbitration rules (e.g., those of the HKIAC, ICC, SIAC, etc.) and national laws impose certain standards for challenging arbitrators. For instance, the challenge procedure typically requires that:

- Grounds for challenge are reasonable and based on specific criteria (e.g., lack of impartiality, independence, or other conflicts of interest).

- Challenge mechanisms are conducted through proper, predefined channels (such as involving an external body, like an arbitral institution, or a court).

- Flipping a coin: Resolving a challenge through a method like flipping a coin is not generally acceptable, as it would fail to ensure fairness and transparency in resolving such a serious issue. Arbitration institutions and rules have clear guidelines that require arbitrator challenges to be resolved based on substantive reasoning (for example, whether the arbitrator’s independence or impartiality is compromised) and procedural fairness (such as through an independent decision by the remaining members of the tribunal or by an external challenge body).

Thus, while the parties may agree to certain procedures, they cannot make arbitrary or capricious decisions regarding challenges—such as flipping a coin—because this would undermine the integrity of the arbitration process.

1 | 💡 What degree of knowledge is required before you have ‘become aware of circumstances’ justifying a challenge? |

Generally, a party needs to have actual knowledge of the facts or circumstances that could justify a challenge. This means that the party must have a clear and substantiated basis for their belief that an arbitrator is biased or has a conflict of interest. It is not sufficient for a party to merely suspect bias or conflicts—they must be able to point to concrete facts or evidence.

In most cases, the challenge must be made within a reasonable time frame after becoming aware of the circumstances. The challenge may be rejected if the party waits too long to raise the issue, especially if they knew (or should have known) about the potential issue but failed to act promptly.

The standard for “awareness” generally involves a reasonable person test: would a reasonable person in the party’s position have known or recognized the circumstances giving rise to the challenge? If so, the party is expected to challenge the arbitrator promptly.

1 | 💡 What does it mean for the “arbitral tribunal” to determine the challenge? What is the scope and role of the challenged arbitrator in such a challenge vis-à-vis his fellow tribunal members and how do parties manage this? |

When the arbitral tribunal is tasked with determining a challenge to one of its members, the situation is complex. It involves both procedural considerations and potential conflicts of interest.

- Tribunal’s Role: In most arbitration systems, the remaining members of the tribunal (if the challenge is not brought against the entire tribunal) will decide whether the challenged arbitrator should be removed. This process often involves:

- A vote or decision by the other arbitrators on whether the challenge is justified, based on the grounds presented by the challenging party.

- The remaining members are expected to act impartially, but there can be a potential bias in these situations (e.g., if the challenge is against one arbitrator, the others might not want to remove a colleague).

- Challenged Arbitrator’s Role: The challenged arbitrator generally has the right to present their defense and explain why they believe they should remain on the tribunal. However, they may have limited influence in the final decision, especially if the challenge is related to impartiality or conflicts of interest, which call into question their objectivity.

- Conflict of Interest: If the challenge is based on impartiality or independence, the challenged arbitrator may find it difficult to make an objective defense since it directly involves their own credibility.

- How the Parties Manage This:

- Neutral Forum for Decision: In most cases, if the tribunal cannot resolve the challenge internally, the parties may refer the matter to an external body (e.g., the arbitral institution or a national court) for a decision.

- Transparency: The parties need to ensure clear communication throughout the challenge process, especially if the dispute is particularly contentious. If the challenge is against one arbitrator, the parties may need to carefully manage the process, especially if the remaining arbitrators are involved in deciding the challenge.

- Practical Considerations: Often, the parties will agree on an expedited process for handling challenges to avoid unnecessary delays, particularly in cases where the integrity of the tribunal is in question.

In summary, the tribunal’s determination of a challenge is a procedural matter that balances the need for fairness with the practicalities of maintaining the tribunal’s integrity. The challenged arbitrator can defend themselves, but their role is constrained by the need to avoid any appearance of bias, while the remaining arbitrators and parties must carefully manage the process to ensure fairness and procedural efficiency.

3. Institutional Role

HKIAC Rules Art 11

11.9 Unless the arbitrator being challenged resigns or the non- challenging party agrees to the challenge within 15 days from receiving the notice of challenge, HKIAC shall decide on the challenge. Pending the determination of the challenge, the arbitral tribunal (including the challenged arbitrator) may continue the arbitration.

- Notice of Challenge + Answer to Notice of Challenge

- Panel appointed by HKIAC Proceedings Committee

- Recommendation from Panel to Proceedings Committee

- Determination of Proceedings Committee

- Reasons usually given

- No provision as to costs of determination

- No automatic provisions as to timetable in the arbitration

- Protection

C. Avoiding Entitlements to Challenge

HKIAC Administered Rules 2024

13.8 After the arbitral tribunal is constituted, any proposed change or addition by a party to its legal representatives shall be communicated promptly to all other parties, the arbitral tribunal and HKIAC.

13.9 The arbitral tribunal may, after consulting with the parties, take any measure necessary to avoid a conflict of interest arising from a change in party representation, including by excluding the proposed new party representatives from participating in the arbitral proceedings.”

D. Timeline to Challenge Arbitrators

The timing of a challenge to an arbitrator and the status of awards or orders made before the challenge are important aspects of arbitration proceedings.

1. Challenge During Ongoing Arbitration Proceedings

Section 26 of the Arbitration Ordinance (AO) and Article 13(2) & (3) of the UNCITRAL Model Law provide that even if an arbitrator has been challenged, they may continue with the arbitral proceedings and issue an award, despite the pending challenge.