What Our Minds Do When We Read Novels

- Novels are second lives.

- Novels reveal the colors and complexities of our lives and are full of people, faces, and objects we feel we recognize.

- But we never complain of this illusion, this naïveté. On the contrary, just as in some dreams, we want the novel we are reading to continue and hope that this second life will keep evoking in us a consistent sense of reality and authenticity.

- We dream assuming dreams to be real; such is the definition of dreams.

- I know there are many stances we can adopt toward the novel, many ways in which we commit our soul and mind to it, treating it lightly or seriously.

- We read sometimes logically, sometimes with our eyes, sometimes with our imagination, sometimes with a small part of our mind, sometimes the way we want to, sometimes the way the book wants us to, and sometimes with every fiber of our being.

- There was a time in my youth when I completely dedicated myself to novels, reading them intently—even ecstatically. During those years, from the age of eighteen to the age of thirty (1970 to 1982), I wanted to describe what went on in my head and in my soul the way a painter depicts with precision and clarity a vivid, complicated, animated landscape filled with mountains, plains, rocks, woods, and rivers.

- When I read novels in my youth, sometimes a broad, deep, peaceful landscape would appear within me. And sometimes the lights would go out, black and white would sharpen and then separate, and the shadows would stir. Sometimes I would marvel at the feeling that the whole world was made of a quite different light. And sometimes twilight would pervade and cover everything, the whole universe would become a single emotion and a single style, and I would understand that I enjoyed this and would sense that I was reading the book for this particular atmosphere.

- I would feel that the orange armchair I was sitting in, the stinking ashtray beside me, the carpeted room, the children playing soccer in the street yelling at each other, and the ferry whistles from afar were receding from my mind; and that a new world was revealing itself, word by word, sentence by sentence, in front of me. As I read page after page, this new world would crystallize and become clearer, just like those secret drawings which slowly appear when a reagent is poured on them; and lines, shadows, events, and protagonists would come into focus. During these opening moments, everything that delayed my entry into the world of the novel and that impeded my remembering and envisioning the characters, events, and objects would distress and annoy me.

- And while my eyes eagerly scanned the words, I wished, with a blend of impatience and pleasure, that everything would fall promptly into place.

- At such moments, all the doors of my perception would open as wide as possible, like the senses of a timid animal released into a completely alien environment, and my mind would begin to function much faster, almost in a state of panic.

- A little later, the intense and tiring effort would yield results and the broad landscape I wanted to see would open up before me, like a huge continent appearing in all its vividness after the fog lifts.

- Here, the writer’s attention to visual detail, and the reader’s ability to transform words into a large landscape painting through visualization, are decisive.

- And we read such stories just as if we were observing a landscape and, by transforming it in our mind’s eye into a painting, accustoming ourselves to the atmosphere of the scene, letting ourselves be influenced by it, and in fact constantly searching for it.

- If she were able to focus on her novel, she could easily imagine Lady Mary mounting her horse and following the pack of hounds. She would visualize the scene as if she were gazing out a window and would feel herself slowly entering this scene she observes from the outside.

- Most novelists sense that reading the opening pages of a novel is akin to entering a landscape painting.

- The real pleasure of reading a novel starts with the ability to see the world not from the outside but through the eyes of the protagonists living in that world.

- When we read a novel, we oscillate between the long view and fleeting moments, general thoughts and specific events, at a speed which no other literary genre can offer.

- We are now inside the landscape that a short while ago we were gazing at from the outside: in addition to seeing the mountains in our mind’s eye, we feel the coolness of the river and catch the scent of the forest, speak to the protagonists and make our way deeper into the universe of the novel.

- Our mind and our perception work intently, with great rapidity and concentration, carrying out numerous operations simultaneously, but many of us no longer even realize that we are carrying out these operations.

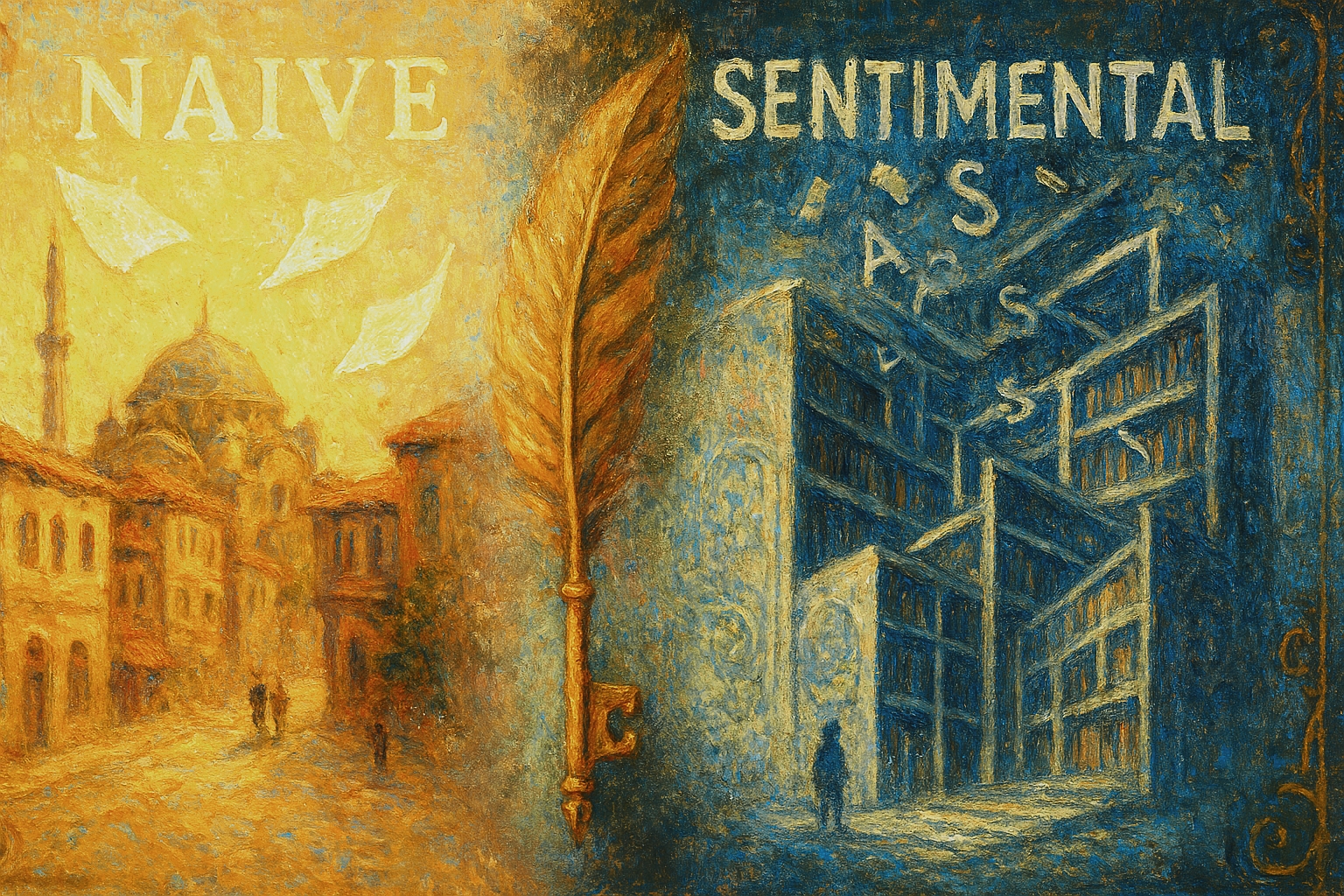

- Let us use the word “naive” to describe this type of sensibility, this type of novelist and novel reader—those who are not at all concerned with the artificial aspects of writing and reading a novel. And let us use the term “reflective” to describe precisely the opposite sensibility: in other words, the readers and writers who are fascinated by the artificiality of the text and its failure to attain reality, and who pay close attention to the methods used in writing novels and to the way our mind works as we read. Being a novelist is the art of being both naive and reflective at the same time.

- The word sentimentalisch in German, used by Schiller to describe the thoughtful, troubled modern poet who has lost his childlike character and naïveté, is somewhat different in meaning from the word “sentimental,” its counterpart in English.

- Naive poets are one with nature; in fact, they are like nature—calm, cruel, and wise. They write poetry spontaneously, almost without thinking, not bothering to consider the intellectual or ethical consequences of their words and paying no attention to what others might say. For them—in contrast to contemporary writers—poetry is like an impression that nature makes upon them quite organically and that never leaves them. Poetry comes spontaneously to naive poets from the natural universe they are part of.

- The naive poet has no doubt that his utterances, words, verse will portray the general landscape, that they will represent it, that they will adequately and thoroughly describe and reveal the meaning of the world—since this meaning is neither distant nor concealed from him.

- The “sentimental” (emotional, reflective) poet is uneasy, above all, in one respect: he is unsure whether his words will encompass reality, whether they will attain it, whether his utteranees will convey the meaning he intends. So he is exceedingly aware of the poem he writes, the methods and techniques he uses, and the artifice involved in his endeavor.

- From the age of seven until I was twenty-two, I constantly painted with the dream of someday becoming a painter, but I had remained a naive artist and had abandoned painting, perhaps after becoming aware of this.

- This dense and provocative work by Schiller will accompany me while I contemplate the art of the novel, reminding me along the way of my own youth, which discreetly oscillated between the “naive” and the “sentimental.”

- When Schiller says, “There are two different types of humanity,” he also wants to say, according to German literary historians, “Those that are naive like Goethe and those that are sentimental like me!”

- Schiller envied Goethe not only for his poetic gifts, but also for his serenity, unaffectedness, egoism, self-confidence, and aristocratic spirit; for the way he effortlessly came up with great and brilliant thoughts; for his ability to be himself; for his simplicity, modesty, and genius; and for his unawareness of all this, precisely in the manner of a child. In contrast, Schiller himself was far more reflective and intellectual, more complex and tormented in his literary activity, far more aware of his literary methods, full of questions and uncertainties regarding them—and felt that these attitudes and traits were more “modern.”

- I try to convince myself that I have found an equilibrium between the naive novelist and the sentimental novelist inside me.

- The naive novelist and the naive reader are like people who sincerely believe that they understand the country and the people they see from the window as the car moves through the landscape.

- In contrast, the sentimental-reflective novelist will say that the view from the car window is limited by the frame and that the windshield is muddy anyway, and he will withdraw into a Beckettian silence.

- We read adventure novels, chivalric novels, cheap novels (detective novels, romance novels, spy novels, and so on may be added to this list) to see what happens next; but we read the modern novel (he meant what we today call the “literary novel”) for its atmosphere.

- Another part of our mind wonders how much of the story the writer tells is real experience and how much is imagination. We ask this question especially in the parts of the novel that arouse our wonder, admiration, and amazement.

- At the heart of the novelist’s craft lies an optimism which thinks that the knowledge we gather from our everyday experience, if given proper form, can become valuable knowledge about reality.

- We make moral judgments about both the choices and the behavior of the protagonists; at the same time, we judge the writer for his moral judgments regarding his characters.

- Let us always keep in mind that the art of the novel yields its finest results not through judging people but through understanding them, and let us avoid being ruled by the judgmental part of our mind. When we read a novel, morality should be a part of the landscape, not something that emanates from within us and targets the characters.

- As our mind performs all of these operations simultaneously, we congratulate ourselves on the knowledge, depth, and understanding we have attained. Especially in novels of high literary quality, the intense relationship we establish with the text seems to us readers to be our own private success.

- In order to find meaning and readerly pleasure in the universe the writer reveals to us, we feel we must search for the novel’s secret center, and we therefore try to embed every detail of the novel in our memory, as if learning each leaf of a tree by heart.

- What sets novels apart from other literary narratives is that they have a secret center. Or, more precisely, they rely on our conviction that there is a center we should search for as we read.

- Novels are narratives open to feelings of guilt, paranoia, and anxiety. The sense of depth which we feel when we read a novel, the illusion that the book immerses us in a three-dimensional universe, stems from the presence of the center, whether real or imaginary.

- Novels present characters that are much more complex than those in epics; they focus on everyday people and delve into all the aspects of everyday life. But they owe these qualities and powers to the presence of a center somewhere in the background, and to the fact that we read them with this kind of hope.

- As the novel reveals to us life’s mundane details and our small fantasies, daily habits, and familiar objects, we read on curiously—in fact, in amazement—because we know they indicate a deeper meaning, a purpose somewhere in the background.

- Novels can address people of the modern era, indeed all humanity, because they are three-dimensional fictions. They can speak of personal experience, the knowledge we acquire through our senses, and at the same time they can provide a fragment of knowledge, an intuition, a clue about the deepest thing—in other words, the center, or what Tolstoy would call the meaning of life (or however we refer to it), that difficult-to-reach place we optimistically think exists.

- The dream of attaining the deepest, dearest knowledge of the world and of life without having to endure the difficulties of philosophy or the social pressures of religion—and doing this on the basis of our own experience, using our own intellect—is a very egalitarian, very democratic kind of hope.

- I read novels as if in a dream state, forgetting everything else, in order to gain knowledge of the world, to construct myself, and to shape my soul.

- Gradually I began to see the fundamental knowledge that the center of the novel presented—knowledge about what kind of place the world was, and about the nature of life, not only in the center but everywhere in the novel.

- I also learned that our journey in this world, the life we spend in cities, streets, houses, rooms, and nature, consists of nothing but a search for a secret meaning which may or may not exist.

- Just like readers searching for the center as they read a novel, or naive young protagonists in a Bildungsroman searching for the meaning of life with curiosity, sincerity, and faith, we will try to progress toward the center of the art of the novel. The broad landscape we move through will take us to the writer, to the idea of fiction and fictionality, to characters in novels, to the narrative plot, to the problem of time, to objects, to seeing, to museums, and to places we cannot yet anticipate—perhaps just like a real novel.

Mr. Pamuk, Did All This Really Happen To You?

Nurturing a love of novels, developing the habit of reading novels, indicates a desire to escape the logic of the single-centered Cartesian world where body and mind, logic and imagination, are placed in opposition.

The second answer suggests that it would be difficult for me—as it so often is for novelists—to convince my readers that they should not equate me with my protagonist; at the same time, it implies that I do not intend to exert a great deal of effort to prove I am not Kemal.

I intended my novel to be perceived as a work of fiction, as a product of the imagination—yet I also wanted readers to assume that the main characters and the story were true.

I have learned through experience that the art of writing a novel is to feel these contradictory desires deeply, but to peacefully continue writing, unperturbed.

Writers and readers have been trying unsuccessfully to come to some agreement on the nature of the novel’s fictionality. I wouldn’t want these words to suggest that I hope such agreement will be reached. On the contrary, the art of the novel draws its power from the absence of a perfect consensus between writer and reader on the understanding of fiction.

In fact, when reading the same novel at two different times, they may have conflicting opinions regarding the extent to which the text might be true to life or, on the other hand, a figment of the imagination.

The impact a novel has on its readers is partly formed, as well, by what critics say about it in newspapers and magazines and by the writer’s own statements aimed at controlling and manipulating the way it is received, read, and enjoyed.

Non-Western authors, who found themselves obliged to fight against prohibitions, taboos, and the repression of authoritarian states, used the borrowed idea of the novel’s fictionality to speak about “truths” they could not openly express—just as the novel had formerly been used in the West.

Eventually, in order to shake off the moral burden of their contradictory stance, which led them into hypocrisy, some non-Western novelists even began to develop a sincere belief in the things they had said.

“Did all this really happen to you?”—a relic of Defoe’s time—has not lost its validity. On the contrary, for the past three hundred years this question has been one of the main forces sustaining the art of the novel and accounting for its popularity.

Just as credulous readers believe that the hero of a novel represents the author himself, or some other actual person, filmgoers believed unquestioningly that the Türkan Şoray on the silver screen represented the Türkan Şoray in real life—and fascinated by the differences between them, they would try to make out which details were true and which were imagined.

Like old men who have reached the point where they can take anything in stride, we smiled at each other for confusing fiction with reality. We sensed that we had fallen under this illusion not because we had forgotten that novels are based on imagination just as much as on fact, but because novels impose this illusion upon readers.

What we were feeling at that moment was—in the terms I’ve proposed in these lectures—the desire to be both “naive” and “sentimental” at the same time. Reading a novel, just like writing one, involves a continual oscillation between these two mindsets.

Our experience probably did not take place on the Moscow–St. Petersburg train, as Anna’s does in Tolstoy’s narrative. But we have had enough similar experiences so that we can share the character’s sensations.

One of the essential pleasures we find in reading novels—just as Anna Karenina does when reading on the train—is that of comparing our life with the lives of others.

There is, of course, no such thing as a perfect mirror. There are only mirrors that perfectly meet our expectations. Every reader who decides to read a novel chooses a mirror according to his or her taste.

What we feel when we open the curtains to let the sunlight in, when we wait for an elevator that refuses to arrive, when we enter a room for the first time, when we brush our teeth, when we hear the sound of thunder, when we smile at someone we hate, when we fall asleep in the shade of a tree—our sensations are both similar to and different from those of other people.

Each novelist has a different way of experiencing, and writing about, the coffee he drinks, the rising of the sun, and his first love. These differences extend to all of the novelist’s heroes. And they form the basis of that novelist’s style and signature.

I had projected my experiences onto my characters: how I feel when I inhale the scent of rain-soaked earth, when I get drunk in a noisy restaurant, when I touch my father’s false teeth after his death, when I regret that I am in love, when I get away with a small lie I have told, when I stand in line in a government office holding a document moist with sweat in my hand, when I see children playing soccer in the street, when I have my hair cut, when I look at pictures of pashas and fruit hanging in greengrocers’ stalls in Istanbul, when I fail my driving test, when I feel sad after everyone has left the resort at the end of summer, when I am unable to get up and leave at the end of a long visit to someone’s home despite the lateness of the hour, when I switch off the chatter of the TV while sitting in a doctor’s waiting room, when I run into an old friend from military service, or when there is a sudden silence in the middle of an entertaining conversation.

But when an intelligent reader told me she had sensed the real-life experience in the novel’s details that “made them mine,” I felt embarrassed, like someone who has confessed intimate things about his soul, like someone whose written confessions have been read by another.

All the works of a novelist are like constellations of stars in which he or she offers tens of thousands of small observations about life—in other words, life experiences based on personal sensations.

Now, I should mention that this great joy of writing and reading novels is obstructed or bypassed by two kinds of readers:

- Completely naive readers, who always read a text as an autobiography or as a sort of a disguised chronicle of lived experience, no matter how many times you warn them that they are reading a novel.

- Completely sentimental-reflective readers, who think that all texts are constructs and fictions anyway, no matter how many times you warn them that they are reading your most candid autobiography.

I must warn you to keep away from such people, because they are immune to the joys of reading novels.

Literary Character, Plot, Time

- It was by taking novels seriously in my youth that I learned to take life seriously. Literary novels persuade us to take life seriously by showing that we in fact have the power to influence events and that our personal decisions shape our lives.

- When we leave aside traditional narratives and begin to read novels, we come to feel that our own world and our choices can be as important as historical events, international wars, and the decisions of kings, pashas, armies, governments, and gods—and that, even more remarkably, our sensations and thoughts have the potential to be far more interesting than any of these.

- As I devoured novels in my youth, I felt a breathtaking sense of freedom and self-confidence.

- Yet the primary focus is not the personality and morality of the leading characters, but the nature of their world. The life of the protagonists, their place in the world, the way they feel, see, and engage with their world—this is the subject of the literary novel.

- Because life is challenging and difficult, we have a strong and legitimate curiosity about the habits and values of the people around us. And the source of our curiosity is by no means literary. (This curiosity also motivates our fondness for gossip and for the latest news from the grapevine.)

- For the seventeenth-century Ottoman travel writer Evliya Çelebi, as for many other writers of the period, the character of the people was a natural feature of the cities he visited, like the climate, the water, and the topography.

- But let’s remember that newspaper horoscopes, which are read and believed by millions of people, are based on the naive view that individuals born around the same time will share the same personality.

- Recall, once again, that Schiller used the word “naive” to describe those people who fail to see the artifice in things, and let’s ask ourselves naively how the world of literature managed to remain so silent and so naive with regard to the character of literary protagonists.

- The most generally accepted reason, which also happens to be the one that Forster advocated, is that literary characters take over the plot, the setting, and the themes when the novel is being written.

- The primary task of the novelist, they believe, is to invent a hero!

- A novel is the product of both an art and a craft.

- The longer the novel, the more difficult it is for the author to plan the details, keep them all in his mind, and successfully create a perception of the story’s center.

- Just like gossip about the character of people we know in real life, eloquent speeches celebrating the unforgettable nature of certain literary heroes are often nothing more than empty rhetoric.

- Since I believe that the essential aim of the art of the novel is to present an accurate depiction of life, let me be forthright.

- People do not actually have as much character as we find portrayed in novels, especially in nineteenth- and twentieth-century novels. I am fifty-seven years old as I write these words. Furthermore, human character is not nearly as important in the shaping of our lives as it is made out to be in the novels and literary criticism of the West.

- More decisive than the character of a novel’s protagonists is how they fit into the surrounding landscape, events, and milieu.

- The strongest initial urges I feel when writing a novel are to make sure I can “see” in words some of the topics and themes, to explore an aspect of life that has never before been depicted, and to be the first to put into words the feelings, thoughts, and circumstances that people who live in the same universe as me are experiencing.

- The character of my novel’s main protagonist is determined the same way a person’s character is formed in life: by the situations and events he lives through. The story or plot is a line that effectively connects the various circumstances I want to narrate. The protagonist is someone who is shaped by these situations and who helps to elucidate them in a telling way.

- If we are to understand someone and make moral observations about the person, we must comprehend how the world appears from that person’s vantage point. And for this, we need both information and imagination.

- The defining question of the art of the novel is not the personality or character of the protagonists, but rather how the universe within the tale appears to them.

- The art of the novel becomes political not when the author expresses political views, but when we make an effort to understand someone who is different from us in terms of culture, class, and gender. This means feeling compassion before passing ethical, cultural, or political judgment.

- Despite all its challenges and the great labor it demands, being a novelist has always seemed a joyful business to me.

- While one corner of my mind is busy creating fictional people, speaking and acting like my heroes, and generally trying to inhabit another person’s skin, a different corner of my mind is carefully assessing the novel as a whole—surveying the overall composition, gauging how the reader will read, interpreting the narrative and the actors, and trying to predict the effect of my sentences.

- Just as there is a limit to the extent we can speak about ourselves as if we were another person, there is also a limit to how much we can identify with another person.

- Another reason I love the art of writing novels is that it forces me to go beyond my own point of view and become someone else. As a novelist, I have identified with others and stepped outside the bounds of my self, acquiring a character I did not formerly possess.

- By writing novels and putting myself in the place of others, I have created a finer and more complex version of myself.

- Reading the novel, we both see the landscape through the heroine’s eyes and know that the heroine is part of the wealth of that landscape. Later on, she will be transformed into an unforgettable sign, a kind of emblem that reminds us of the landscape she is part of.

- What remains in our mind is often the novel’s general layout or comprehensive world, which I refer to as its “landscape.” But the protagonist is the element we feel we remember. So in our imagination his or her name becomes the name of the landscape the novel presents to us.

- What matters is not the individual’s character, but the way in which he or she reacts to the manifold forms of the world—each color, each event, each fruit and blossom, everything our senses bring to us.

- What makes Anna unforgettable is the accuracy of the myriad small details. We come to see, feel, and engage with everything just as much as she does—the snowy night outside, the interior of the compartment, the novel she is reading (or trying unsuccessfully to read).

- The novelist develops his heroes in accordance with the topics he wants to research, explore, and relate, and with the life experiences he wishes to make the focus of his imagination and creativity.

- The desire to explore particular topics comes first. Only then do novelists conceive the figures who would be most suitable for elucidating these topics.

- I naively believe I can show how the minds of other novelists function when those writers construct a novel, so long as I sincerely convey my own experience of reading and writing novels.

- In other words, there is a naive side of me that believes I can express to you, my readers, the sentimental-reflective side of my being which is preoccupied with the technical aspects of the novel.

- According to Aristotle, just as there are indivisible and irreducible atoms, there are also indivisible moments; and the line that connects these countless moments is called Time.

- The plot of a novel is the line that connects the large and small indivisible narrative units.

- The golden rule of the art of the novel, stemming from the novel’s own inner structure: the reader should be left with the impression that even a description of a setting entirely devoid of people or an object completely peripheral to the story is a necessary extension of the emotional, sensual, and psychological world of the protagonists.

- In a good novel, a great novel, descriptions of the landscape, various objects, embedded tales, slight digressions—everything makes us feel the moods, habits, and character of the protagonists. Let us imagine a novel as a sea made up of these irreducible nerve endings, these moments—the units that inspire the writer—and let us never forget that every point contains a bit of the protagonists’ soul.

- In novels, time is not the linear and objective time indicated by Aristotle, but the subjective time of the protagonists.

- It is difficult for both the writer and the readers to distance themselves from the protagonists in order to distinguish objective time and get an overall view of the novel.

- Reading a novel involves entering the landscape and missing the general picture. It is only by entering the general landscape through the minute details of our life and our emotions that we acquire the strength and freedom to understand at all.

- So I always feel that I should connect the thousands of small dots that compose a novel not by drawing a straight line, but by drawing zigzags between them.

- In a novel, objects, furniture, rooms, streets, landscapes, trees, the forest, the weather, the view outside the window—everything appears to us as a function of the protagonists’ thoughts and feelings, formed from the general landscape of the novel.